In 1957, George Dunbar made one of the best decisions of his life. He joined IBM. "I feel so lucky, because IBM was looking for a photographer, and I was hired as their first," he told DCD.

"They were buying all of their photography from commercial studios - mainly employee pictures because they had an extensive employee magazine, a country club, a golf course, a baseball diamond, lawn bowling, and tennis courts," he explained.

"I was pretty lucky to get that job and be the first photographer there."

This feature appeared on the cover of Issue 44 of the DCD Magazine. Subscribe for free today to support our journalism

Art from mainframes

Dunbar would go on to work with IBM out of Canada for an incredible 32 years, from 1957 to 1989, amassing an enormous portfolio that documents a little-studied computing revolution. Now those records could be lost.

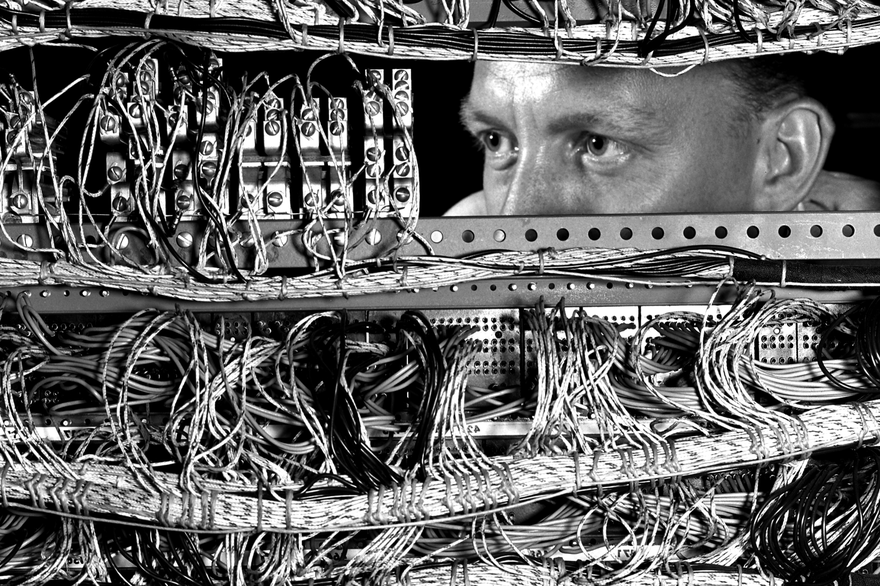

"I was there when they had the huge mainframe computers in 1957, and I saw all the changes in computers over the coming years. Now, of course, I'm amazed that people are walking around with a computer in their pockets,” he said. “It's more powerful than those mainframes."

Dunbar's photography is powerful in its own way, too. Given what could be seen as a rather lifeless and corporate remit, he managed to inject art and beauty into his job.

"I would create my own assignments," he said. "I photographed all the manufacturing procedures, something the company never had done before. They were quite surprised to see the kind of photographs I was able to produce, they really ate those up and started publishing it in newspapers and magazines, and in some of the trade magazines."

He also had to do what he called 'grip-and-grins,' the more traditional photographs of white men in white shirts and dark suits shaking hands. "I took thousands of those, I never really enjoyed that," he said.

Where he took joy was in photographing the systems, as well as use cases. "I was sent in to do assembly plants, steel mills, and all kinds of industries across Canada, and see all those technical operations."

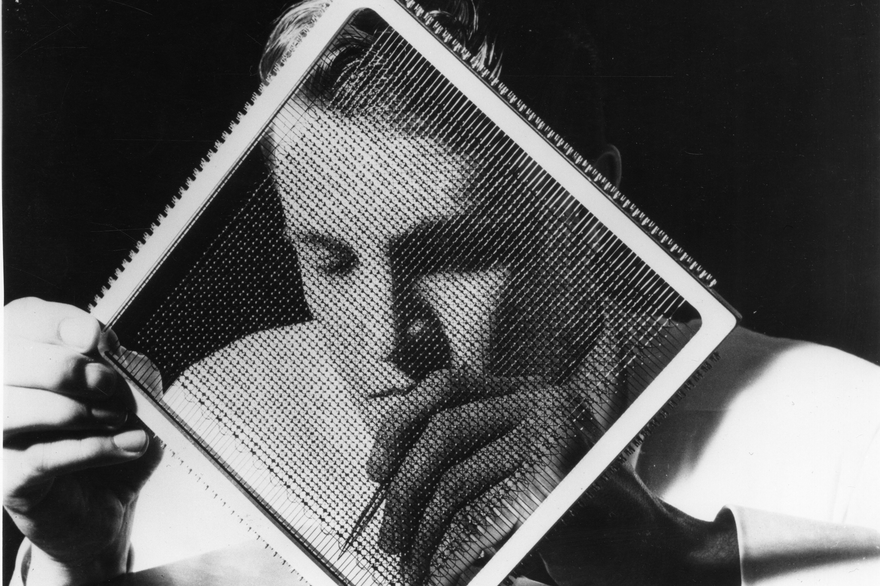

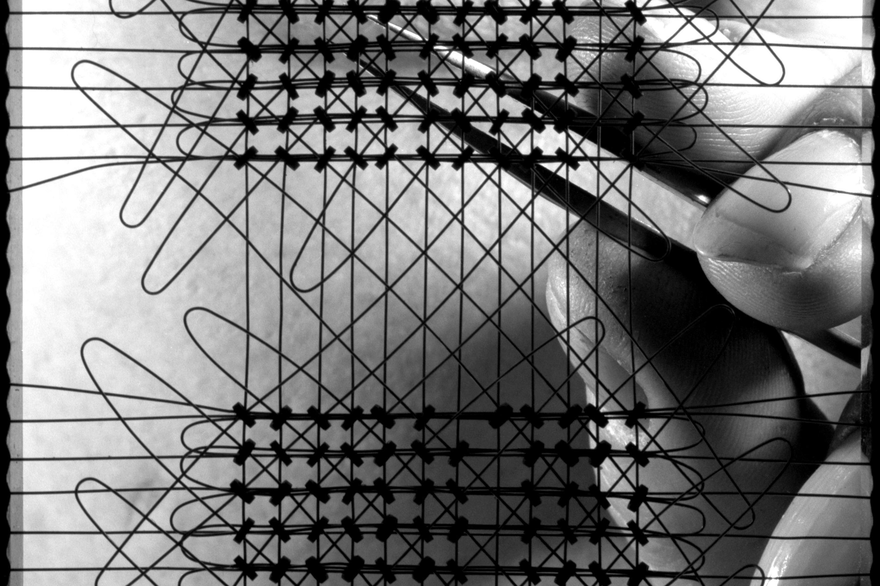

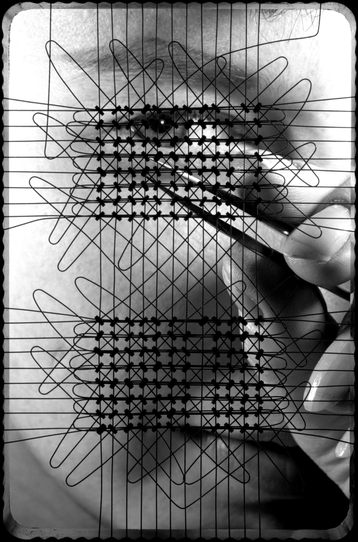

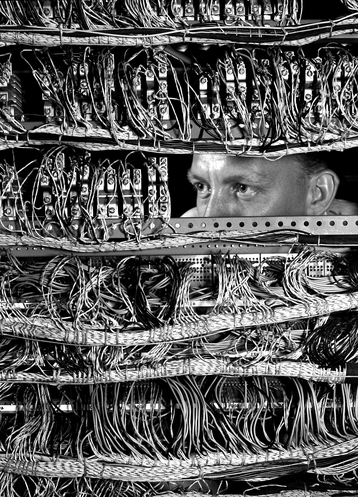

Among his favorite works are his images of memory cores. "I've seen a lot of pictures of memory cores. They are all basically close-ups. I took a photograph with a face behind it, which I think was very unique."

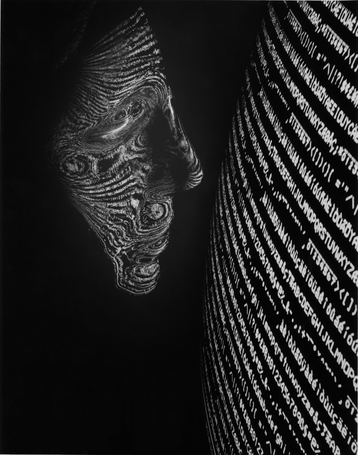

Another was his ‘glass head’ photograph, where he used a prop his son brought home and "I saw that it would pick up the reflection from the computer screen. I played with it for a while and that was what I came up with."

Despite the photo being from the early 1970s, Dunbar still thinks it could be relevant. "I would hope someday that that photograph might be used to illustrate artificial intelligence," he said, noting that nebulous modern concepts like AI are much harder to visualize than the physical hardware of his day. "Fortunately, it's not my challenge anymore."

Today's photographers have another challenge: "Data centers and servers are not as interesting as they used to be in the old days, right? They're just grey boxes, filled with rows and rows of grey boxes. There's nothing to take a photograph of these days, because they're not very interesting."

Back then, they were much more visually fascinating, he said. "We had them in glassed rooms, open to the public in some cases, and you could see the spinning tape drives and a lot of the mechanisms that work."

The physicality of the servers and storage was a side effect of the level of technology of the day. The open and glassed nature was a choice.

"A lot of computer rooms were in show windows in the ground floor of an IBM office building," he said.

"It was kind of a promotional thing. People in the streets of Toronto or Montreal would always see a big IBM computer room on Main Street," with the mainframes used to sell the concept first to enterprises, and then solidify the company's brand with consumers for PCs.

One IBM data center was even located at the ground floor of a major Toronto hotel. When The Beatles came to town, they stayed at the hotel, with crowds filling the street as the IBM facility whirred in the background.

“It was a huge corporate propaganda win,” Professor Zbigniew Stachniak recalls. As an associate professor at the department of Computer Science and Engineering at York University, now retired, Stachniak has spent decades trying to piece together a history of the Canadian computing industry.

After writing a book about one of the first personal computers in Inventing the PC: the MCM/70 Story, Stachniak began to delve into "what else was done in Canada, and it turns out that there were very many world firsts and significant achievements on the hardware side, computer services side, and on the software side.”

In an industry of perpetual change and product launches, forever in search of the next big thing, it's easy to forget the early history of computing - especially outside of the much-studied and mythologized Silicon Valley.

It’s also easy to forget that, for a time, there was one undisputed tech king: IBM.

"When I mentioned IBM to my students, they were really thinking 'why am I talking about a company nobody really knows much about?,' I have to explain that in 1960s, 70s, 80s, and well into the 90s, IBM was the company. It was the Apple, Google, Microsoft, and everything combined."

The technology king

IBM began in 1911 as an amalgamation of four companies, under the clunky name 'the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company.'

"It was a very convoluted name that basically consisted of the original companies, but a Canadian subsidiary called International Business Machines was formed in 1917," Stachniak explained. "It began being used in adverts, and by 1924, it was the name of the whole company."

With this early change, IBM's Canadian division played a crucial role in ensuring the corporation’s success, helping usher in the information age as we know it.

In turn, IBM's business in the country swelled, bringing commercial computers, early artificial intelligence systems, and vast data centers to Canada for the first time. But the history of IBM's impact in Canada has been little studied, and mostly forgotten.

Stachniak believes that the key to understanding some of that impact lies in Dunbar’s work.

Over his lengthy career, Dunbar took tens of thousands of photographs and films, many of which are of artistic or historical significance. "Some of them were awarded prizes, but they were not distributed widely,” Stachniak said.

"There is this purely artistic experimentation in his work - if you look at some of these photographs, it's just amazing, you will immediately want it hanging on your wall."

Stachniak regrets that Dunbar was unable to have his images published outside of IBM and technical periodicals, "because he would be a world-renowned photographer by now, that's no doubt.

"In my life, I saw so many corporate technological photographs of various technologies, and it's not often that you see that type of photography."

Unfortunately, most of that photography is sitting undisturbed in an air-conditioned room, with little chance of it ever seeing the world.

In the early 2000s, Dunbar offered to give a large portion of his life's work to Stachniak, who runs the York University Computer Museum in Toronto. But the idea initially fizzled due to copyright issues and funding concerns.

A few years later, Stachniak tried to get some money from IBM Canada for his museum. "They listened and said ‘we will let you know, but also would you look at these boxes of photographs in the next room?’”

There, Stachniak discovered Dunbar’s work, along with other photographs, trade magazines, newsletters, and films from the IBM film studio Dunbar set up. He was astonished at the neglected treasure trove, and kept visiting. “Eventually, they got tired of me coming,” he recalled. Instead, they offered to donate it to his museum. “IBM really wanted to get rid of it,” he said.

But his museum lacked the necessary air-conditioned rooms for the proper storage of old materials, and the two groups settled on donating it to the York University’s Special Collections archive, where they now remain.

The hope was that, with funding, the many thousands of pieces would be digitized for the world to see. But, instead, they languish as low-priority material in an overstretched archive.

Representatives of the archive declined to comment on the record, but one employee spoke to DCD under the condition of anonymity. "It is still unprocessed, we just don't have the staff to deal with it," they said, adding that the archive’s backlog has ballooned with the pandemic.

"We're still, I believe, trying to get some money out of IBM to have it processed. But the minute it was no longer on their loading dock and entered our vault it became less of their problem and more of ours."

Saved from the trash

The person said that IBM "didn't want it to go into the garbage. But at the same time, they don't seem to be assisting us and getting it further along."

IBM declined to comment on its efforts to help digitize the images or fund the archiving process, but DCD understands it is no longer in communications with the archive. Thousands of images chronicling IBM’s golden era and a fascinating part of Canadian history remain in limbo. It is not clear if they will ever see the light of day.

“There's no other collection that visually shows the computing industry in Canada,” Dunbar said. “And I tried to emphasize to them that this is a very valuable historical collection - it's the history of computing in Canada for 30 years. And it is just nowhere else.”

A few photographs have been viewed by outside eyes, some of which were exhibited by Stachniak as a limited event at the museum, titled ‘Portraits of a Digital Canada.’ A few others are published here, for the first time in more than thirty years, if ever. The rest, however, risk being lost to history.

Should these photos be all that remains, Dunbar hopes that they stay with you. "I've always judged photographs by how long a person will look at them," he said. "If you give them a stack of photographs, and they go through them, giving each a one-second glance and go on to the next one, then their photographs are not very good.

"But if the person goes through the stack of photographs, and suddenly pauses at one and says, 'Wow, this is something I'm going to look at for a while,' that indicates that it's a good photograph," he said. "And that's what I've always tried to do - something different that will cause the viewer's attention to last a little more than just one second."