We all know that IT is the epitome of a regulated industry. Everything we use in IT, from the components and cables to the servers and chillers, has to comply with hundreds of environmental and other regulations from countless cities, states, provinces, and countries.

We have to satisfy communications, electrical and safety standards; manage and reduce toxic materials; improve energy efficiency; and, ensure that equipment can be recycled. Compliance with this constantly evolving regulatory landscape is a major challenge that puts a substantial burden on manufacturers.

But when you examine the landscape of IT, one mission critical area has largely escaped this level of regulatory scrutiny and the social accountability that drives it: data centers. If the sector does not take charge of its own sustainability, that will quickly change as data centers become just as heavily regulated as any other aspect of IT.

Now, you’re probably thinking that data centers are already regulated. After all, they have to comply with construction codes, for example. While that may be true, governments and the communities they represent are just beginning to catch up with the need for environmental, zoning and land use regulation.

Let’s face facts: the data center industry is experiencing explosive growth, with accelerating new construction worldwide. Our data centers have a consequential environmental impact, but have so far largely flown under the regulatory radar. As that footprint dramatically expands in both size and geographic scope, it will no longer be ignored.

A typical 20MW data center:

- Uses electricity equal to the needs of 13,000 homes;

- Consumes 160 million gallons of water per year1 (typically potable water) that could otherwise supply 17,000 homes;

- Evaporates most of the water into the air and dumps the rest into the public wastewater treatment system;

- Handles large volumes of chemical refrigerants that are among the most harmful to the climate and the ozone layers (which are continuously at risk of bans and phase-outs);

- Makes a lot of noise; and,

- Takes up valuable real estate in commercial districts.

Any PUE will do

Today’s data center practices assume none of this matters as long as a municipality can supply sufficient power and water, not to mention refrigerants, water treatment chemicals, and land can readily be bought. Data center operators can build a data center of any PUE, with any amount of water consumption and wastewater production they want. There’s no oversight or restriction no ‘gas guzzler’ tax, compliance limits, or even an objective standard for energy, water, chemical or resource efficiency.

Of course, many claim that we’re already working hard to minimize our environmental impact. After all, some data center operators are leading the way with procurements of wind and solar (although it is a mystery why procurement of emissions-free power from nuclear, hydro, geothermal, and emerging CCUS carbon-capture systems are off the table).

In addition, a few data center operators are attempting to incrementally mitigate water consumption and also buying carbon credits. While such efforts are well intentioned, at best, they are making only a marginal improvement. They miss the fundamental problem: why does the industry needlessly waste so much energy and water in the first place? Where are the nationally and globally recognized standards for power or water efficiency that most other sectors operate under?

What about power utilization efficiency or PUE? Although PUE is an ISO standard (ISO/IEC 30134-2:2016), there’s no oversight or enforcement of PUE outcomes. Many organizations employ ways to game the system to make their data center’s PUE look better than it really is. And PUE isn’t a great metric when comparing data centers in different climates or data centers with different levels of server utilization. Even more problematic is water utilization efficiency or WUE. This has been around for a decade2, yet very few organizations even mention it.

This situation won’t last. Governments will – probably very soon – react. Imagine some worst case scenarios:

- Dozens and then hundreds of governments, from cities to countries, each come up with their own unique program of environmental regulations for data centers;

- The business and PR nightmare of having to abandon a project simply because a city is trying to place sensible limits on power and water consumption;

- A state or county decides to block or put a moratorium on all new data center construction due to uncertainty over the impact on availability of power and fresh water for households, and important settings such as schools, hospitals, agriculture and sanitation.

We’ve already seen some of the first moves.

In 2019, Amsterdam put a moratorium on data center construction3 in order to develop an intelligent plan for future growth. That caused serious damage to the Dutch data center sector and led to the establishment of specific zones for construction, development and reservation of adequate power supplies, and the establishment of a PUE standard of 1.2 for all new construction, after which new data center construction resumed4. Today Dublin, Mesa, Capetown, and Singapore are all working out how to manage similar issues.

So what happens when a government takes years to examine the problem? As leaders in the industry, we know more about data center construction and operations than anyone in government. We also know that our ability to reduce power and water consumption is rapidly evolving, and that statutory standards set today will rapidly become obsolete.

What should we do to make sure data centers are as efficient as possible, as agile as possible, and able to grow in line with demand?

We should self-regulate. Attempts at this have been made in the past by various organizations, but we’re at a point now where the effort must be fully accomplished. Many will point to our industry history and say government regulation to some degree is inevitable, and maybe it’s true. But successful self-regulation would be a far better informed and implementable alternative.

What should that look like?

First, let’s start by being fully transparent about all of our individual and sectoral environmental impacts. Let the four biggest data center equipment manufacturers, five hyperscalers, and 20 Fortune 100 companies get together, form an association, and agree to share all of the environmental data that pertains to the data center – power, water, refrigerant and chemical use, noise, everything. Let’s be totally open.

Second, that association should collectively agree on what to do with the data. Working groups can define metrics that are appropriate. Let’s not compare a hyperscale data center to a Fortune 500 data center because hyperscale designs may not even use UPSs, for example.

Third, let’s take the metrics and set standards, appropriate for groups of data centers, and re-examine them every year. If PUE is easy to game, let’s come up with another measure, set a standard, and use it as a measuring stick to drive incremental improvements over time. Let’s partner with equipment manufacturers to create agreed upon standard technologies for measuring power and water consumption, and use them.

Fourth, let’s set up an industry body that agrees to oversight of industry adherence to the standards we agree to. There are precedents for this. Recreational diving is a great example of an industry that globally self-regulates, with the dive card being a passport to scuba diving anywhere in the world5. Universities are often accredited by private, not-for-profit trade organizations. Hospitals and other health care facilities are accredited by independent bodies.

Ultimately, the data center industry could come up with a way to ensure an industry certification or mark for data center environmental impact, like the UL or CE marks. Organizations with the mark can prove that they meet a set of criteria, giving them added credibility as they discuss new site placement and construction with government agencies.

We’ve seen this approach beginning to emerge in Europe as a result of the Amsterdam situation. The Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact6 is a first step toward industry self-regulation, with an aim of making the data center industry climate neutral by 2030. It’s an emerging initiative with dozens of signatories that has real potential for making a difference. But while climate change is important, it is only one measure of the data center ESG. Contribution to harmful air pollution, burden on public drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, noise, recycling, and development footprint also directly affect the communities where we operate. Similar initiatives need to emerge in North America and other locations with significant data center growth — and our leading data center providers need to make that happen as soon as possible.

What’s the alternative? If we don’t self-regulate, what happens? We already know.

- Multiple governments could put a halt to new construction;

- They could spend years investigating possibilities and crafting standards, influenced by organizations and lobbyists, with loop holes and limitations;

- We could end up with a complex patchwork of regulations,restrictions and taxes;

- The regulations might remove incentives to push the envelope toward efficiency that goes beyond the standard;

- We could lose control over what we do;

- We could have a harder time minimizing our environmental impact.

Wait for government regulation, or regulate ourselves? The answer is clear. Let’s pull together and work on doing the right thing for ourselves, our customers, and the planet. It’s time to move forward.

References:

1. Uptime Institute Research: Water Scarcity Could Put Your Data Center at Risk

4. DCD: Opinion - Two years after the Amsterdam moratorium, where does its data center industry stand?

More...

-

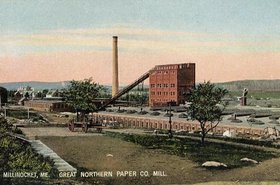

Nautilus gets involved in paper mill site cleanup

Barge builder rolls up its sleeves to clear up debris on land

-

Nautilus Data Technologies launches first floating data center

Company opens first data center on a barge in Stockton, California

-

The Sustainability Supplement

How data centers can help the climate