In line with almost everyone’s analysis, Uptime's research into where enterprises are putting their workloads has found a very strong move of workloads to the public cloud, much of which then ends up in running, wholly or in part, in colocation data centers.

But at the same time, we found that a core of workloads is not on the move. In fact, by 2021, about half of all workloads will still be in enterprise data centers, and three-quarters will be placed at sites where the IT will still be under enterprise control. (NB: We are not including consumer-based services such as Netflix or Snapchat.)

Why is this? One reason came across clearly at the recent KPMG resilience week in London. A panel of senior financial services executives were asked about their use of cloud services. All expressed concerns about the lack of transparency and some, about contracts/service levels. One summed up it: "Either cloud providers will have to be more transparent, or its going to be pretty difficult for them to pick up financial services business."

Cloud needs to open up

That discussion in London echoed contributions made an earlier meeting of financial services operators organized by Uptime Institute, this time in Paris. Again, almost all those in the room said they would not put core services in the public cloud - for mostly the same reasons (although privacy and competition were also cited). Note that all are using private cloud in either their own data centers or in colocation sites.

The resiliency and openness of public cloud services (and software-as-a-service) is one of the areas addressed in the Uptime Institute Hybrid Resiliency Assessment (HRA), a service launched earlier this year.

In the HRA protocol, operators are guided in how to assess the resiliency of the services they are using, and, where appropriate, advised to consider if they have the appropriate level of assurances and/or information.

But the truth is, for some industries and applications, the public cloud operators and the core financial services industries are far apart in what they expect from each other. In Europe, for example, guidance for banking and the use of cloud from the EBA (European Banking Authority) says that for critical functions, banks should expect to have access and audit rights to their IT venues. Such levels of access are simply not part of the cloud operating model - at least today.

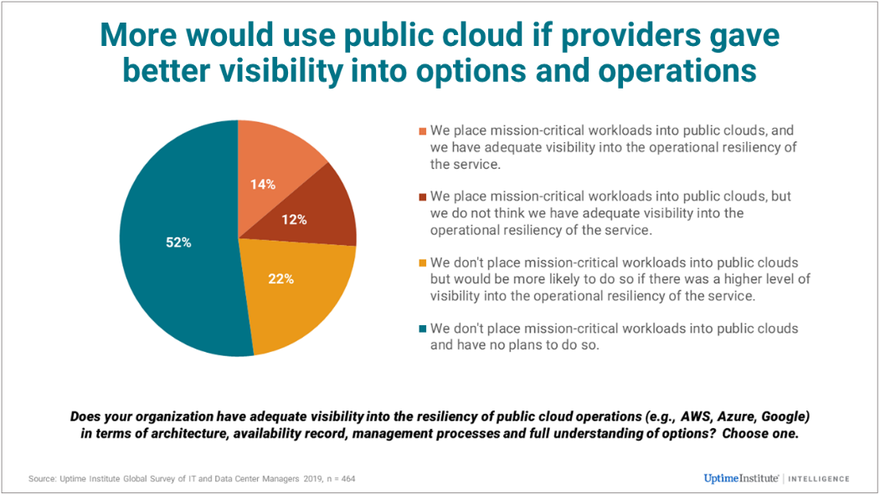

It is probably no surprise that banking is constrained in its use of the cloud. But what about the broader picture for mission-critical applications? In our 2019 survey, transparency and service levels very clearly emerged as a reason not to use the cloud. Only one in six organizations said they used the public cloud and were happy with the transparency; a bigger number - one in five - don’t use the cloud but said they would be more likely to do so if there were greater transparency.

It is not just about transparency. One chief information officer recently told us: “I am not concerned about cloud resiliency, and not so much with transparency. I want to be sure that when there is a problem, the cloud company is alongside us, working with us to help us recover. I don’t want to see an Instagram message or a tweet telling me they are aware.”

At present, the cloud companies can scarcely keep up with demand, but that will change. At some point, a big provider will decide there is a big opportunity and take the unilateral step to be more open and offer better service level agreements, while maintaining the public (shared) architecture. When this happens, private and public clouds will look little more like each other.