The Greenpeace and Amazon renewable-energy spat continues, albeit somewhat abated. The environmental pressure group has been a long-term critic of the cloud provider, while Amazon has tended to remain silent.

In last year’s Clicking Clean report , Greenpeace said:

“Amazon Web Services, which provides the infrastructure for a significant part of the internet, remains among the dirtiest and least transparent companies in the sector, far behind its major competitors, with zero reporting of its energy or environmental footprint to any source or stakeholder.”

The 2015 update of Clicking Clean has this to say:

“Amazon’s adoption of a 100 percent renewable energy goal, while potentially significant, lacks basic transparency and, unlike similar commitments from Apple, Facebook or Google, does not yet appear to be guiding Amazon’s investment decisions toward renewable energy and away from coal.”

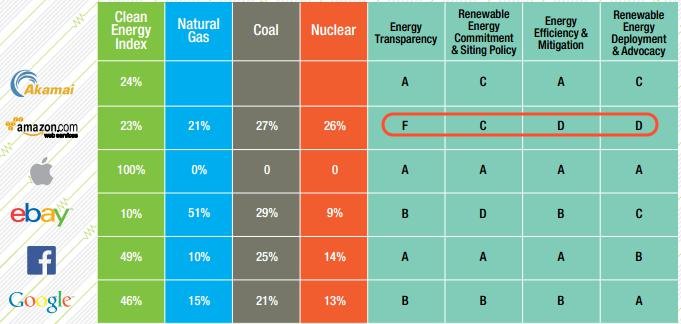

That sounds like an improvement. However, in the somewhat controversial scorecard developed by Greenpeace, the highest grade obtained by Amazon was a “C” in Renewable Energy Commitment and Siting Policy.

The details of the Greenpeace survey have been well-reported. What’s missing is Amazon’s side of the story. I asked the people at Amazon about this and was referred to the company’s AWS and Sustainable Energy webpage. “We’ve made a lot of progress on this commitment,” says the post. “As of April 2015, approximately 25 percent of the power consumed by our global infrastructure comes from renewable energy sources. We have a goal of increasing this to at least 40 percent by the end of 2016.”

I’m afraid the closest we’re going to get to a discussion of what Amazon thinks about the Greenpeace report and renewable energy is the personal blog entry Greenpeace, Renewable Energy, and Data Centers of James Hamilton, vice president and distinguished engineer at Amazon Web Services. Hamilton makes a personal response to the 2015 Greenpeace report, and it would be remiss of us not to point out that the opinions expressed are Hamilton’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of his current or past employers.

If Hamilton were to conduct a survey

Hamilton admits he is less than excited by the Greenpeace report, partially because of the report’s format, and partially because of the report’s content. He feels Greenpeace has focused on the wrong areas, and says if he did a survey, it would cover the following:

Resource utilization: To Hamilton, this is by far the biggest lever in the industry. The carbon cost to produce servers, storage, and networking equipment, and the carbon impact to power it all is largely wasted, because it is idle. “Common server utilization rates average between 10 and 20 percent across the industry,” writes Hamilton. “Turned around, that’s 80 percent to 90 percent wastage and there is no topic more important to address around data center environmental impact than utilization.”

Hamilton asserts the industry could easily deliver major improvements. One example of such an improvement would be Autoscale. Facebook engineers and software developers figured out how to save energy by load-balancing server production clusters.

Energy efficiency: “An energy-efficient facility is good, but a 100 percent renewable energy facility is better,” advise the authors of this Apple environment report. Hamilton agrees but with qualifications. “I have this as the number two largest lever to reduce the environmental impact of data centers,” mentions Hamilton. “Efficiency is important because all power consumption, regardless of the source, has an impact on the environment. So our first commitment, as an industry and as consumers, has to be to only consume that which we need and to always be looking for ways to get the job done by consuming less.”

Hamilton goes on to say that technically “Energy Efficiency and Mitigation” is part of the Greenpeace report, but he does not agree with the assessment: “If you get a chance, read through the results on this category and see if they match your take on where data center energy efficiency innovation is under way and which companies are driving the biggest environmental gains.”

Go where the problems are: It is good that Greenpeace focuses on data-center power consumption, says Hamilton. But he feels the report’s authors lose their way by focusing on the best-known five percent of data-center power consumption and not offering a solution for the remaining 95 percent. “Even more important, the decision by this report’s authors to completely ignore energy conservation in the evaluation criteria just doesn’t make sense for the environment,” Hamilton adds. “A key recommendation completely missing from the report is that the largest and most effective single lever to green IT usage is to move resources to the cloud where utilization is higher and the much higher scale supports direct renewable power purchasing agreements.”

As evidence, Hamilton offers Greenpeace’s 2011 report How Dirty is Your Data. “It was highly critical of Facebook and yet, at the time, they (Facebook) were estimated to have only 100,000 servers and were clearly one of the most energy-efficient operators in the industry,” argues Hamilton. “At the time of the 2011 Greenpeace survey, I was blogging about Facebook’s energy-efficiency innovations, so it is a mystery to me why they were being held up in the report as one of the worst environmental offenders.”

Renewable energy commitment: Hamilton feels Greenpeace covered this well and he agrees with their focus.

Proposed solutions

According to Hamilton, Greenpeace places too much emphasis on renewable energy. There needs to be a multifaceted approach. Besides reducing the use of nonrenewable power, Hamilton suggests the following:

- Resource utilization: “The Greenpeace report ignores energy conservation as a component,” mentions Hamilton. “Energy conservation needs to be part of any solution.”

- Usage disparity: Large data-center operations do use a lot of power, but it is still only 5 percent of the total consumed. “The smaller operations, when aggregated, use most of the power,” explains Hamilton. “I would advocate cloud computing as a way to green these thousands and thousands of often ‘closet-sized’ data centers.”

One last concern

To Hamilton, the four areas selected by Greenpeace seem to miss the mark and are difficult to objectively measure. “My biggest concern is that great scores can be achieved in the Greenpeace report while doing a poor job on taking care of the environment, and worse, the opposite can happen as well,” said Hamilton. “Companies can be rated poorly while doing great things environmentally. These four areas just don’t look like the most effective places to focus if really trying to green the data center industry.”

Being such a complex subject — environmentally and economically — it seems to me, any and all dialogue between environmental groups such as Greenpeace, data-center operators (commercial and private, big and small), and power utilities will benefit us all.