The world’s digital infrastructure has been built by the paranoid. At every turn, equipment is duplicated, routes are triplicated, fuel reserves are over-filled. Astronomical sums are spent on building layers and layers of safety into the system, as suspicious minds game out various scenarios that could put the precious flow of data at risk.

And yet, there remains one giant bottleneck, a quirk of geography and geopolitics, that is anything but redundant.

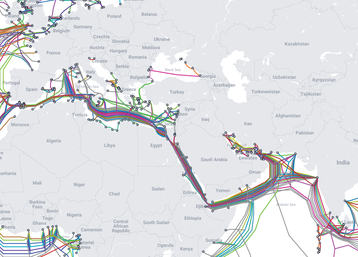

If you take a map of the world’s submarine cable infrastructure, responsible for shuttling data between nations and entire continents, and zoom in on the Middle East, you will notice something striking: Everything goes through Egypt.

Data traveling to and from Europe and Asia, as well as Northern Africa and the Middle East itself, has just one route.

Coming from the Gulf of Aden, cables snake up along the Red Sea, and into the Gulf of Suez. There, they make landfall in Egypt, traversing little more than a hundred miles, before breaking out into the Mediterranean Sea.

"There's no way a network operator would design their network like this under ideal conditions, right?" said Paul Brodsky, senior analyst at Telegeography, best known for its maps of cable routes. "They don't like having everything funneled through one place."

This route concentration is a concern for reliability, putting an estimated 17 percent of the world's Internet traffic in the hands of one country, and in one shallow and narrow sea. But it is also a concern for businesses, which have to contend with a monopoly.

To get through Egypt, companies have to pay exorbitant fees to state-owned Telecom Egypt. Prices have risen dramatically, amid claims of corruption, but operators have had little choice but to pay. At least until now.

This feature appeared in the latest issue of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

The only route

The story of Egypt’s submarine stranglehold is hard to tell. Several analysts declined to talk on the record due to business relationships with Telecom Egypt. Cable providers either declined to talk, or did not respond to requests for comment. “I am afraid I won’t be open to discuss the Egyptian submarine cable bottleneck due to certain concerns,” another industry figure said, declining to elaborate.

In Egypt itself, it’s even harder to talk about the cable situation. In 2019, the TV host of local news program 90 minutes, Ossama Kamal, accused the government of corruption with the way it charges submarine cable operators, and said it risked destroying its position as the gateway between Asia and Europe.

Immediately following the broadcast, he was suspended from his show, fined, and forced to apologize. He did not respond to requests for comment.

Whether Telecom Egypt abuses its market dominance is a matter of debate - some, speaking on background, called fees extortionate. Others accepted it as the cost of business for using the most logical route through the Middle East, with more than a dozen major cables choosing to go across the country.

Egypt’s position as a critical communications node between East and West dates all the way back to the colonial era, and remains, due to a few simple reasons.

First is geography: It’s the shortest stretch of land between the Mediterranean and Arabian seas, hence the creation of the Suez Canal for shipping. Network operators like to avoid needlessly traveling across land, with its expensive owners and pesky national sovereignties that need to be dealt with.

Then comes geopolitics. Do Western companies want data to travel through Iran? How about Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria? Operators like to steer clear of sanctioned nations, or active war zones, so they are off most people’s preferred routes - although some have still tried, but we’ll get to that later. There is one other journey they could take, but that too, we shall save.

Finally, there are market forces. "Once you establish a route and everybody's using it, the cost goes down as more people use it," Doug Madory, director of Internet analysis at Kentik, explained. "So it's really hard not to use it, and it's hard to break out of what ends up being the most selected path.

“With this Egypt chokepoint, obviously the geographic layout is the number one reason, but then once it gets established, it's super hard to break out because then there's so many cables, so many lines, so much infrastructure built along that path."

With this in its favor, Telecom Egypt has been able to charge huge fees - between 6.6 percent and 17.4 percent of its total revenues came from cable fees between 2008 to 2019, according to Submarine Cable Networks. The founder of SCN declined to comment.

It took a while for the state telco to realize it was sitting on a goldmine: It used to sell a perpetual license for somewhere in the ballpark of $100k. Then they moved to a monthly fee, a source told DCD. "Then they

said 'oh no, we want to have the transit costs, where people pay by volume of traffic.’ So if tomorrow traffic doubles for a telecom, they get double pay or whatever the tiering system is," Madory said. "I feel like that was too far - people started to revolt, although what can you do? It's not like there's another Egypt you can go to."

Another industry figure called the fees "ridiculous." An SCN report found that 12 submarine cables crossing Egypt paid the telco at least $369 million for Indefeasible Right of Use, with additional Operation and Maintenance (O&M) charges during the lifetime - however, it is not clear if this is before the telco tried to shift to charging more for more traffic.

Warzones and warnings

The lack of diversity and huge costs of traveling through Egypt have led some to seek alternative routes - some of which appear to have been scams, others of which were ill-advised.

In 2010, Saudi Telecom Company teamed up with Jordan Telecom Group (JTG), Turk Telekom, and Syria Telecom for an ambitious terrestrial cable spanning some 2,530km (1,570mi). JADI - named so because it would link Jeddah, Amman, Damascus, and Istanbul - had a short life. "There was a lot of hype around this being an alternative to Egypt," Madory recalled. "We were able to test the line and see that it was up… and then it went down."

His contact at Jordan Telecom, sent from France by parent company Orange, let him know why: "It got blown up." Just months after JADI launched, the Syrian Civil War broke out. To bring the cable back online, someone would have had to repair it in the middle of a warzone, with no guarantee it wouldn't just immediately be broken.

"I don't think anybody's ever mentioned that route again," Madory said. "But there was a brief period that existed."

Another alternative came in the EPEG cable, stretching an impressive 10,000km (6,200mi), primarily across land. Announced in 2011, it set off from Oman, briefly crossing the Gulf of Oman and into Iran. From there, it traveled north, up through Azerbaijan, and into Russia, where it veered west via Ukraine, Hungary, and Austria, before terminating in Frankfurt, Germany. Madory remembers asking network operators about the cable back in 2013, where they told him it was too expensive.

But EPEG had a unique opportunity: That year, the Seacom cable went down after thieves tried to steal copper by setting fire to its terrestrial connection traveling through Egypt. Just a few months later, divers were arrested off the coast of Alexandria for damaging SeaMeWe-4 in a purported effort to get scrap metal (this is a story that has raised many eyebrows in the industry, but alternative explanations are not known).

EPEG raced to take advantage of the trouble, pushing forward its launch, but the price was still offputting. There were other challenges, namely its route. "Iran was still volatile after the Arab Spring," Madory said.

Curiously, it managed to find one major customer, the state telco of Bahrain, Batelco - despite deeply strained relations, and just a year after Bahrain had accused Iran of inciting upheaval in the small state.

Madory has worked with the Bahraini telecoms regulator, so let them know about the strange decision.

"I said: ‘I don't have a dog in this fight, but we think you should care that you are sending your government stuff through Iran.’ People usually flip out over that kind of stuff.'"

Instead, the regulator told him it couldn't do anything, but asked him to talk to the Batelco engineers. Iran’s telco wasn’t much better when it tried to sell access to EPEG: "My contacts in the region said they were quite inflexible on price, so they walked away," Madory said.

With the cable also passing through Russia, it's far from a preferred route for US allies.

Its website is no longer active, but archived versions state it had a capacity of 540 gigabytes per second - not much compared to today's cables. However, it may still be active: Madory noticed Internet outages in Iran that were tied to cable cuts in Ukraine due to the invasion, and he thinks it must have been EPEG.

None of these efforts have proved a viable alternative to the Egyptian route. But there exists another way.

Answers in Aqaba

If you head up the Red Sea, you have a choice as you reach the tip of Egypt's South Sinai province. Head northwest and you will travel up the busy Suez Gulf, topped by the eponymous canal. Or you could turn northeast, passing through the narrow Straits of Tiran and into the Gulf of Aqaba. At its end, you will have another choice.

Virtually the entire west of the gulf is still Egypt, almost all of the east is Saudi Arabia (which does not border the Mediterranean). But right at the tip, crowded into just a few dozen kilometers are the edges of Israel and Jordan, the former of which does open up to the Mediterranean on its other side.

Travel along this gulf is treacherous, prone to sudden squalls in a narrow channel filled with islands and coral reefs. What little sea-side territory Israel and Jordan own is precious, with a focus on port or beach access.

But it would be possible to get a cable through there, if only you had the money and the political power to get Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Jordan to work together.

Enter Google.

In 2020, it was revealed that the company was working on the $400 million Blue-Raman cable traveling from Mumbai, India, across the Indian Ocean, touching on Djibouti and Oman, before going to Saudi Arabia, and then ending up at the Jordanian port of Aqaba. It then goes into Israel, out to the Mediterranean, and across to Genoa, Italy.

A tale of two halves

Blue-Raman is a single cable, but Google pretends it is two - the Raman portion covering the section from India to Jordan, and the Blue section going from Jordan, through Israel and Italy.

This act of theater is thought to be just so that Israel and Saudi Arabia can pretend that they don't share a cable, even though they do. Google won't confirm the reason for the double name, nor how much of the cable runs across Saudi territory, declining to comment for this piece.

The name switch, lots of money, and an intense behind-the-scenes transnational lobbying effort allowed Google to pull off a geopolitical coup that will offer the first real alternative to Egypt since the Internet began.

The cable is expected to go live in 2024, offering 16 fiber optic pairs to Google, and partners Omantel and Telecom Italia Sparkle.

"In time, consortium members hope to make additional landings and connect the two systems through terrestrial network assets," Bikash Koley, VP and head of Google Cloud for Telecommunications global networking, said when the project was officially announced in 2021.

The company made no mention of Egypt, just hinting at the bottleneck by saying that "developing additional network capacity and routes is critical to Google users and customers around the globe."

Unsurprisingly, operators and industry figures were again reticent to disclose the background of how the cable came to be. One said: “Google has been able to negotiate something with the various parts… I should probably stop talking.”

Madory was more open: "They're a bottomless pit of money, so if they want it, they can get it."

Helping matters is the fact that Google Cloud is building data centers in both Saudi Arabia and Israel.

In the former, after slightly delaying its announcement due to the state-sanctioned murder of Jamal Khashoggi, it teamed up with state-owned fossil fuel giant Saudi Aramco to launch data centers in a joint venture.

In echoes of the Blue-Raman wordplay, Google claims that it can work with oil company Aramco without helping the company's oil business, because it is working with Aramco's technology division.

When Google previously contacted DCD to make this clarification, we pointed out Aramco’s supposed non-oil-related technology arm does not have any website or public presence. At this point, Google stopped responding.

The cloud region has also been criticized by 39 human rights groups due to Saudi Arabia's well-documented record of illegally surveilling its own citizens, and torturing dissidents.

Over in Israel, Google is building its fourth data center, after winning a $1.2bn government cloud contract (jointly with AWS). That contract has also been criticized by human rights groups and some of Google's own staff, due to the supported agencies' treatment of Palestinians.

Israel equally has a long history of state surveillance and nation-state cyber attacks. The cable is far from perfect, having to travel through nations with a poor track record of espionage and surveillance. They also are nations that do not talk to each other, which sits oddly with sharing a communications cable.

Saudi Arabia has not recognized Israel since it gained independence in 1948, although they do work together behind-the-scenes in the Arab-Israeli alliance against Iran.

While Google's own backdoor meetings may never become public, what is clear is that it was able to pull off what others have failed to do, charting a new route through the Middle East.

Concern at home

In Egypt, it sparked consternation. It is this contract that caused the journalist Kamal to make his comments, arguing that the greed and corruption of officials charging such high fees for transit was what caused Google to go elsewhere. This, he and others argue, could spell the end of what was an easy revenue stream for the country.

Telegeography's Brodsky is careful to not overstate the impact. "It's not like Egypt is suddenly out of the submarine cable business, quite the opposite,” he said. “There's plenty of cables that have either very recently launched or are in planning or development right now that are absolutely going to run through Egypt: The 2Africa cable just launched to Africa, which is going to be the longest submarine cable system in the world by far. That's planned to run through Egypt.

“Africa-1, IEX, SeaMeWe-6 - these are all new cables that may come online in the next several years. They all transit Egypt. So it's not like Egypt is suddenly being abandoned."

He also noted that Egypt's submarine cable concentration is not as dire as it first appears - they do take some different routes across land, and benefit from four cable landing stations in the north and three in the south, offering some level of diversity.

Telecom Egypt claims there is sufficient diversity so that if one cable goes, the others will be unaffected. However, a June cable cut to AAE-1 appeared to also impact SeaMeWe-5, potentially suggesting more overlap than disclosed. The outage impacted huge swathes of Europe, East Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, as well as all the major cloud providers.

"Cuts happen," Brodsky said. "They happen all the time, and to the best of us."

It's also unlikely that Egypt itself would decide to exercise too much power over the cables - just as with the Suez Canal, it knows it can keep collecting revenues as long as it doesn't threaten to shut things down.

At the peak of the Arab Spring, as protestors flooded into Tahrir Square, President Hosni Mubarak cut Internet services to the country, enacting a digital blackout. Wild and desperate, these were his final days in power, but he knew not to mess with international cables or the Suez Canal - both flowed freely.

It is unlikely any Egyptian government would change that equation. The same cannot be said for individuals. In April 2022, a coordinated attack was carried out in Paris, with multiple cables connecting the French city to Lyon, Strasbourg, and Lille physically cut in several places. It caused major outages across the country - and no one knows who did it.

A similar event in Egypt would wreak a lot more havoc on the global Internet, as would any damage that could come from more revolutions or civil wars - as we saw with the JADI cable in Syria.

These may seem unlikely, but the job of those providing constant uptime is to prepare for such eventualities. Issues with the Suez Canal were dismissed as groundless fears, until a single ship - the Ever Given - wedged itself in the middle of the channel, disrupting global commerce.

Google's cable would be immune to such events but, of course, will itself be vulnerable to where it travels through. "Many-country terrestrial lines are hard to pull off," Madory said. "If anything goes wrong in any of the countries..."

But at least Blue-Raman changes the calculation by being at risk of different events than every other cable that travels through the Middle East.

What comes next

It is not clear how long Google and its partners will maintain a monopoly on its alternative route. The hope is that, by helping lay the geopolitical and infrastructural groundwork, it will spark investment in more cables through Israel.

In 2020, the CEO of Israeli telecoms company Cellcom, Avi Gabbay, said that it hoped to build a terrestrial fiber cable from Israel to Dubai. It then hopes to launch a submarine cable from Israel over to the EU.

However, no other details about the project were made public and Gabbay was fired by shareholders in 2021 for being too independent. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

This July, Saudi Arabia signed a strategic partnership with Greece to explore a submarine cable. It appears to be very early days for the system, which may not come to pass, and its route has not been disclosed. Passage through Egypt still remains the most likely, but Saudi Arabia could choose Israel - however, then it would have to accept that it is a single cable they share. Saudi government representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

Eventually, however, more cable systems will replicate the passage Google found. But they will augment what goes through Egypt, not replace them. They may also help lower the prices Telecom Egypt charges, making it a more reasonable investment.

Because, if those charges are normalized, Egypt still represents the most logical route - the shortest stretch of land before the safety of the open sea.