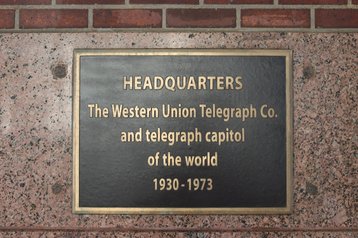

Aside from a few modernizations such as LED bulbs, the lobby of 60 Hudson Street in New York City looks largely the same as it did in the 1930s, down even to a row of original phone booths kept preserved by the building manager.

But little else has remained unchanged about this landmark of data center history. While it has always been a telecoms hub, today the building is a major data center interconnection point, ready to undergo its latest phase as old tenants move out and new ones move in. Today the ducts that run throughout the building and surrounding area carry packets of data along fiber instead of packets of mail.

Since the mid-1990s, 60 Hudson and a number of peer facilities have kept the Internet’s lights on, providing interconnection capabilities unrivaled anywhere else in the world.

But as the data center market increasingly evolves towards purpose-built, high-density cloud and Edge facilities, can these historic legacy facilities keep up with modern demands?

Carrier hotels: A slice of data center history

There is no industry standard definition of a carrier hotel versus merely a data center with a meet-me room (MMR). But, generally, the term is reserved for the facilities where metro fiber carriers meet long-haul carriers – and the number of network providers numbers in the dozens.

That means these facilities are often located centrally in major metros, in large multi-story buildings. The compact and built-up nature of inner-city development means it's not unusual to retrofit existing real estate for digital infrastructure – it's common to see carrier hotels housed in buildings dating back more than 100 years.

“Carrier hotels, they really start with the meet-me rooms,” says Gerald Marshall, CEO of Netrality Data Centers. “They have long been the connectivity hub, forming a critical mass of carriers which form the foundation of an ecosystem.”

“If you look at a fiber map where carrier hotels are located, all the lines run into each other [at these locations],” he adds. "Whereas if you look at just a commodity data center, you might see one or two lines of fiber optic cables going in. So it's a staggering difference between a carrier hotel and just a normal data center.”

These buildings will often host multiple colocation providers and offer interconnections via one or more MMRs. The presence of a large number of carriers is the major draw of these facilities, but takes time to reach the acritical mass.

Many of the most interconnected facilities in the US date back to the mid-1990s and the deregulation of the telecoms sector, and have spent decades building up their connectivity amid shifting technology waves.

Amid ever-growing hyperscale grey box builds in the countryside and containerized Edge facilities built in various nooks and crannies, many carrier hotels retain some old-world character, humming away quietly in defiance of a market constantly changing around them.

“These carrier hotel locations, they're artifacts of how the Internet evolved,” says DataBank CEO Raul K. Martynek. “But they are still the connectivity bedrock of the modern Internet. And these buildings are irreplaceable.”

The key differentiator, he says, is the number of fiber networks. Carrier hotel locations work out as the termination of fiber connections in the inner exchange of IP and voice traffic.

“They appeal to that carrier and content ecosystem because the Internet is a network of networks, and at some point, these networks have to physically touch. And where they physically touch is in these carrier hotel locations.”

Mike Hollands, VP of market development at Digital Realty, adds: “The role of a carrier hotel has never been more important. Carrier hotels act as pulsating hubs, enabling diverse networks to interconnect, creating a robust and resilient infrastructure for global connectivity. As data demands surge exponentially, carrier hotels continue to play an increasingly vital role.”

Legacy benefits, legacy challenges

Some of the earliest interconnection facilities remain in operation today. As well as 60 Hudson Street, the likes of 111 8th and 32 Avenue of the Americas in New York City are still humming away, many having launched in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

In California, for example, MAE-West - housed in the Market Post Tower at 55 South Market in San Jose - was one of the earliest Internet exchanges. Launched in 1994 and previously operated by MCI Worldcom, CoreSite still operates the facility as its 80,000 sq ft SV1 data center with access to some 65 networks.

529 Bryant Street in Palo Alto was originally the home of the Palo Alto Internet Exchange (PAIX). It was a local telephone company building that was developed as an independent carrier-neutral exchange point in 1996. PAIX was owned and operated by Digital Equipment Corporation; AboveNet acquired PAIX in 1999 and sold it to Switch and Data in 2003. Today the facility is operated by Equinix as its SV8 data center.

MAE-East, the first Internet exchange, was launched at 1919 Gallows Road in Vienna, Virginia, in a cinder-block room in an underground parking garage. The exchange moved to Ashburn in Loudoun County in the late 1990s, and the site was closed down in 2009. Equinix’s nearby DC2 facility at 21715 Filigree Court – built in 2000 and part of a 12-building campus – took the mantle and today hosts more than 200 networks. Today 1919 Gallows is a Cogent office.

Many of the other major interconnection hubs in the US – One Wilshire in Los Angeles California, 350 East Cermak in Chicago, Illinois, and NAP of the Americas in Miami, Florida – also date back to the early 2000s.

“The challenge with the carrier hotels is the fact that they're not purpose-built to be data centers, generally speaking,” says Netrality’s Marshall. “They're there because they happen to be on the intersection of Main and Main for Metro and long haul fiber, and these carriers knocked on the door and said, ‘Can we come into your building and put some gear in there.’ And that's often how they evolved.

“These buildings weren't custom-built to be data centers, and therefore they are limited in their ability to accommodate some of these high-density uses, especially when they're on a larger scale.”

Sander Gjoka, VP of construction at HudsonIX, notes buildings like 60 Hudson – where his company operates several floors – present regular challenges.

“There's some great things about the building, but there's also some challenging things about it, one of them being ceiling heights,” he says. “From slab to slab is about 14ft. Once you put the raised floor in and you’ve got beams and all that stuff in the way, heights get very tight.

“And also just because it's a brick building, the floor loading can be challenging from a structural perspective. We invest a lot of money into steel and spent millions of dollars reinforcing it.”

Demand for fiber conduit is so high in 60 Hudson the building has decommissioned two elevator shafts in order to feed in connectivity capabilities.

The fact that these facilities are usually located in inner city metros also means a lot of red tape and bureaucratic processes to get things done.

“What I envy [with new builds] is that from shovel to turning up a server is six months,” says HudsonIX CEO Tom Brown. “I wish we would operate like that in the city.”

The ongoing renaissance of the carrier hotel

Because of their age, it is rare for new space and power to become available at some of the most sought-after carrier hotels. When it does, it is often snapped up quickly.

But where most colocation data centers will be full of appliances of every variety, increasingly carrier hotels customers are focused on critical connectivity hardware.

“You don't see a lot of racks of storage systems or compute servers in these carrier hotel locations; there are predominantly Ciena gear and Infinera gear,” says DataBank’s Martynek, whose company operates out of some of the biggest carrier hotels in the country and operates several in tier-two markets.

“In the 1990s and early 2000s, you had the networks in these locations, but you also had customers putting in regular compute and storage systems. But over time all those non-critical workloads have migrated out of these buildings, and more and more network workloads have migrated into these buildings.”

And whether that compute and storage is going to the cloud, on-premise, or colo, data still needs to travel from A to B (and C and beyond), almost always traveling through these carrier hotels.

That importance means space remains at a premium in these sites. HudsonIX – founded in 2011 as DataGryd and recently renamed after being acquired by investment firm Cordiant – is doubling down on its presence in the building.

The company currently occupies around 170,000 sq ft (15,800 sqm) in the building – including one suite leased to Digital Realty – and recently took up an option on an additional 120,000 sq ft of data center space and 15MW of capacity that will bring its presence at 60 Hudson to four floors.

“A little over 70 percent of all traffic in the Northeast Corridor – going from Boston, all the way down to Washington, DC – comes through this building in one shape or another,” says HudsonIX’s Gjoka. “90 percent of this building is communications. This is the center of the wheel in New York; the 111 8th Avenues, 85th 10ths, 32 Avenue of the Americas, they are all spokes off of this building.”

The company is currently building out five 1MW data halls – known as MegaSuites – on the sixth floor. The first hall launched in 2021 and work on the next hall is due to begin in the summer for a Q4 completion date. The vacated floors were previously office space occupied by the New York Departments of Buildings and Correction; HudsonIX’s Brown describes the floors as a “clean slate” that gives the company a rare chance to build new data center space without the need for a retrofit of existing infrastructure.

2022 saw Equinix surprisingly announce its NY8 data center in 60 Hudson was to be closed, its customers migrated, and the company exit the iconic building. Equinix’s lease at the site – where it offered around 10,073 sq ft (936 sqm) of colocation space – ended around September 2022.

Equinix’s stated reason for the exit – alongside several other facilities including the 56 Marietta carrier hotel in Atlanta, Georgia – was: “In some cases, the leased properties are in facilities that may not meet the future operational, expansion, or sustainability needs of our customers or our corporate standards.”

The company retains a presence in NYC close to 60 Hudson at 111 8th Avenue as its NY9 facility. In response to DCD’s requests for comment, Equinix described carrier hotels as “strategic assets” and an “important part of data center strategies” to support connectivity needs.

When asked if leaving 60 Hudson and 56 Marietta negatively impacts its customers, an Equinix company spokesperson said:

“On the contrary, this decision shows we are very in tune with our business, our customers’ needs, and how the marketplace is evolving. We believe our customers at these sites will be better served in other IBXs in each metro where they can take full advantage of our rich ecosystems. This also will allow us to reallocate and sharpen our investments to other facilities.”

Beyond its given reason, many of the people DCD spoke to said the company likely thought it could offer better differentiation by using its large New Jersey campus in Secaucus, rather than playing second fiddle as a smaller tenant in 60 Hudson.

The space was quickly snapped up by local colo provider NYI – which already has a presence in the building – in partnership with QTD Systems, led by former Telx CTO and DataGryd/HudsonIX CEO, Peter Feldman.

“There are people that will show you gorgeous, perfect meet-me rooms that were built to a high spec fairly recently,” NYI COO Phillip Koblence tells DCD. “But where the actual traffic is going, most of it is happening in places that exist because they have always existed, in facilities people have used over the course of the last 20 years and still continue to use.”

NYI already operated around 21,000 sq ft (1,950 sqm) of space in 60 Hudson after acquiring Sirius Telecommunications’ assets at the iconic building in 2018. The company is also looking to bring the 75 Broad Street carrier hotel back into the fold after the facility came close to closing down entirely.

“We're trying to make the legacy sites cool again,” Koblence jokes.

The role of carrier hotels in 2023: The broker between cloud and Edge

In the realm of technology, legacy is often a dirty word. Instead of its common use to suggest lasting impact, it implies old, inefficient, outdated, verging on obsolete. In some ways, carrier hotels represent both; they are often filled with old equipment and operate at low densities, with PUEs that pale in comparison to today’s most-efficient facilities. They are often difficult to update due to being in heavily-regulated inner-city metros.

Given these limitations, one could question the value of these historic oddities in the era of Edge and cloud. Admittedly, most of these can be fixed with enough time, money, and determination – Hudson IX has spent large amounts of money reinforcing floors and upgrading the building’s power infrastructure in 60 Hudson – but is it worth spending so much on a relic?

“Carrier hotels are absolutely critical,” says HudsonIX’s Brown. “I have a simple definition for the Edge, and that's where the application meets the network. And you're gonna see more and more applications being driven to the aggregation points like legacy carrier hotels.”

Many others buy into the same theory. These are some of the most in-demand facilities in the industry, offering connectivity benefits near-impossible to replicate elsewhere because of their years in operation.

Carriers continue to use carrier hotels as a way to connect to each others’ networks, and will likely continue to do so for years.

But as the rest of the data center and cloud sector continues to evolve, putting many static, latency-tolerant workloads in these buildings doesn’t make sense. And as these workloads move out, a new breed of low-latency workloads are moving in.

“Carrier hotels are not just limited to the present, they are at the forefront of shaping the future data center landscape,” says Digital Realty’s Hollands. “With the rise of emerging technologies such as Edge computing and 5G, carrier hotels will become even more instrumental, acting as pivotal points for Edge deployments, enabling low-latency processing and supporting the massive data influx generated by the Internet of Things (IoT) devices, as well as artificial intelligence (AI).”

The likes of gaming, 5G, financial services, voice, and video communications, CDNs and live streaming services, IoT/machine-to-machine, and other low-latency workloads are increasingly coming into carrier hotels for latency and load balancing.

As well as acting as established Edge data centers themselves in densely populated locations with little room for new facilities, carrier hotels can become an aggregation point for data en route from more remote facilities to the cloud.

For example, Dish – which has been rushing to reach a 70 percent 5G coverage milestone in 2023 - was present across a number of the carrier hotel facilities DCD visited in New York, with newly established cages and IT hardware. Dish is a major AWS customer, so much of that data aggregated in NYC is likely directed back to Amazon’s cloud facilities in Virginia.

The new availability of space in 60 Hudson is allowing some customers to overcome traditional power limitations in long-toothed carrier hotels. HudsonIX is building out space for a gaming client. Unusually for the building, the data hall in question – built on one of the floors vacated by the Department of Corrections – won’t be using raised floors in order to accommodate higher-density workloads.

“That original use case as an interconnected and centralized aggregation point for metro fiber routing data to long haul fiber to send to faraway places is still critical today,” says Netrality’s Marshall. “While this need continues to drive robust demand, more and more latency-sensitive information is being processed locally and sent right back to the region.

“We're not seeing the workloads of the past go away, but we're seeing the new workloads join. Before, the carrier hotel was aggregating data and sending it off to where it needed to go. Now, with these latency-sensitive use cases, more data is being stored and processed in the carrier hotel, and then sent right back to the local end users that are sometimes just machines needing instructions.”

Is the market hospitable to new carrier hotels?

Demand for these kinds of interconnect-rich acilities remains high, but availability is often low, and finding the right locations to establish new facilities with the same offerings can be difficult. The fiber overbuilds of the dotcom boom are long over, and in today’s capex-cautious world, finding new sites with the kind of fiber-rich ecosystems carrier hotels have just isn’t as feasible as it once was.

Difficult though it may be to create that network gravity, companies do still regularly pop up hoping to create new carrier hotels, often in secondary markets where there is potentially more opportunity. But efforts like these can take years to come to fruition, even in a sector used to long timelines.

“It's a double-edged sword,” says Ray Sidler, CEO and co-founder of DataVerge, a data center operator in Brooklyn that has built up a network of 30 carriers over the course of 20 years. “How do you get the clients, and how do you get the carriers? The clients don't come if the carriers aren't there, and the carriers don't come if the clients aren't there. It takes forever.”

In Kansas City, Netrality has built up its 1102 Grand facility from 30 networks when it took over the site around a decade ago to more than 140 today. Known as the Bryant Building and built in the early 1930s, the 26-story property offers 7MW across 156,120 sq ft.

Netrality’s Marshall adds: “I think that it's nearly impossible to create a carrier hotel from scratch. It’s really difficult to get a critical mass of customers to pick up and move to a new place.”

The company is now aiming to supplement its existing carrier hotel in Kansas City with a directly-connected facility that can offer a more modern home to customers.

The goal, he says, is to meet the high-density demands of the customers, but also their sustainability requirements – including waterless cooling. As the new facility is located 10 miles away from 1102 Grand, it allows for active replication between the two facilities and offers a new location for facilities that want the connectivity but might be able to tolerate an extra millisecond of latency.

“We took a building that was partially office and partially warehouse and we're converting it into a data center that we are going to connect via a fiber optic umbilical cord to our 1102 Grand in Downtown Kansas City.”

“This new facility is capable of much more much higher density power, it's got higher ceilings, we can put in the new most modern power distribution and cooling systems, as well as waterless cooling.”

While existing companies are always eyeing new opportunities, new entrants are also trying to make a name for themselves, both in established markets and new ones. Last year Polaris Group-owned Spencer Building Carrier Hotel announced plans to develop a whole new carrier hotel in Vancouver, Canada adjacent to the city’s existing 555 West Hastings Street carrier hotel.

In November 2022, Detroit real estate firm Bedrock announced plans for a new carrier hotel in the Michigan city, at 615 West Lafayette, in partnership with digital infrastructure platform provider Raeden. Formerly the Detroit News Building, the six-story, 311,800 sq ft (29,000 sqm) 615 West Lafayette was built around 1915-1916. Detroit News left the building around 2014 and sold the site to Bedrock for an undisclosed sum.

Hunter Newby, an interconnection pioneer who co-founded Telx and Netrality, aims to develop a huge amount of new small interconnection hubs across parts of America where connectivity is currently lacking. His Newby Ventures business is partnering with non-profit organization Connected Nation to build 125 Internet Exchange Points in 43 states and four US territories, including in 14 states that currently have no carrier-neutral connectivity point at all.

“The markets have coalesced around a small number of assets in these markets,” says DataBank’s Martynek. “The huge markets like New York, Chicago, and Dallas, tend to have three carrier hotels. In smaller markets like Pittsburgh or Cleveland, there might only be one or two.

“The Internet continues to grow, bandwidth continues to grow, and you still need more fiber terminations,” he adds. “But these buildings are old, and it's hard to bring new power and cooling into them.”

“So what you're seeing now is that interconnect fabric is starting to decentralize. You see it happening all over the country, where newer interconnect homes are emerging. If we want to serve customers in Minneapolis, we need to serve them out of Minneapolis, and not out of Chicago or out of Ashburn or out of California, which is what happens today.”

Martynek says things are changing. Up to 90 percent of data in Minneapolis is currently being peered in Chicago, he says. In a decade, he suggests that most of that will be peered in Minneapolis: “It’s a change in the shape and gravity of the Internet.”

But while some traffic might drain from the major hubs to these secondary and tertiary markets, the continued global growth in data means it will be replaced ten-fold by even more data created in those existing carrier hotels’ local markets.

While many of these new carrier hotels might lack the history and legacy of a 60 Hudson or a One Wilshire, they will be no less important in their local areas than some of those historic buildings.

“Over the next 10 years, I think you'll see the incremental capacity that gets consumed on the Internet will be more pronounced in places like San Diego, in Minneapolis, in Kansas City.

“But it's additive; it's not at the expense of the existing carrier hotels, because ultimately these are the most efficient places to exchange traffic due to the unparalleled number of networks available in these buildings.”