This article is stored on a hard drive, a solid state drive, or on paper. Years from now, if it proves popular enough, it might live on tape. Then, when someone wants to read it, the data will be transferred to light, sent across fiber cables, and beamed to the user’s local device.

It’s a setup we’re all used to, with data kept on static storage systems, before being converted to photons for communication. But why not keep it as light the whole time?

“We just keep light moving around and around,” CEO Ohad Harlev explained. In theory, this could prove far more power-efficient than storage on a fixed medium: “What anybody else is doing in megawatts, we're doing in kilowatts,” he said.

This article appeared in Issue 40 of the DCD>Magazine. Subscribe for free today

Light as a storage solution

Storing an exabyte on Earth in conventional hard drives could take megawatts, although the latest 6.5W, 18Tbyte units could reduce the average power for the actual drives themselves to as low as 360kW - and of course long term storage would not use active powered media.

By comparison, LyteLoop proposes it would take 35kW to 40kW to store exabytes of data in space. And then, of course, there’s the energy it would take to get the satellites up there.

Bizarre as LyteLoop’s idea sounds, the concept has deep roots. In the late 1940s, the first computers, EDSAC and EDVAC, used “delay lines” which stored data as a wave reflected and circulated in columns of mercury.

LyteLoop has a patent (US20170280211A1) for a system that recirculates light between satellites, amplifying it and regenerating it as required.

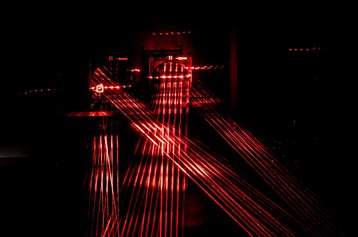

The company has made earthbound prototypes, including one in 2018 which used a coil of 2,000 kilometers (1,242 miles) of fiber. "We stored over a gigabyte for about 30 days - that means that each packet traveled over 300 billion kilometers, that's the equivalent of 17 times what Voyager One has been traveling for the last 40 years.”

The company also proposes an earthbound system called Tube, that attempts to reproduce the spaceborne version, in which a long light path is created in metal chambers 10m to 100m long, using reflections and angle multiplexing, where light is reflected from a large number of apertures, designed to increase the distance of travel.

LyteLoop’s site proposes a 100m long near-vacuum Tube, 30m wide, which could hold 10 exabytes.

"And then you can take the same cube and miniaturize it to anything in the centimeters to meters range," Harlev claimed, "You could put it in a data center, or in a vehicle. And that can store anywhere between 10s of gigabytes to hundreds of petabytes, depending on the form factor." LyteLoop’s site describes a Cell that would be 2.5m long and hold 200 petabytes.

Each time the light hops, a small amount of energy is lost. In its most recent prototype, the company has managed to do 432 hops on a single beam, but hopes to reach 5,000 hops by June.

The technology uses optical networking equipment, but with a difference, said Harlev: "We are talking with ourselves, we know what packets we're sending, and we're sending them to us. So we can eliminate a lot of the digital processes needed in the telecom industry. We're able to do it very efficiently both on the hardware side of the components and digital processes needed."

These earthbound systems require effort to recreate something which LyteLoop can get for free, in the vast expanse above the atmosphere, says Harlev. LyteLoop’s proposed network of 300 small satellites would continually shift light between them, before beaming it to a third-party satellite that would handle uplink and downlink.

"We're focused on doing space first, both because I think it adds more value to the customers with different value propositions," Harlev explained. "But on top of that, we are slightly cheating - because if we do the space, then we have developed all the technology we need for the [terrestrial solutions]."

There is still a long way to go before it gets to that point. Operating in stealth for the past five years, LyteLoop now hopes to launch six prototype satellites within three years. "And the final product ready for deployment in five," Harlev said.

The project has become significantly more feasible, Harlev noted, thanks to the dramatic drop in rocket launch costs, as well as satellite uplink/downlink. "Between the $40m we just raised, and what we raised in the past, we have enough to hire all the people that we need and to launch the six satellites in space," he said, even assuming no further rocket launch discounts happen.

Should all go to plan, the 300 satellites should be able to store around two exabytes of data, which could increase as more systems are added to the constellation. LyteLoop plans to own and operate its satellites as a "cloud above the clouds" storage provider, and then later sell the terrestrial versions as hardware.

The company will have to convince customers to trust a novel storage concept - and the idea of shunting their data beyond the surly bonds of Earth.

"I believe that you need to show the benefits of [a new approach] overwhelmingly, to be adopted," Harlev admitted. "People may keep a copy on the ground for a while."

Another advantage Harlev sees is the vast need for data to go somewhere. We have insane, mind-boggling, terrifying quantities of it squirreled away in corporate data centers, sloshing between cloud providers, and stored in great reams of tape.

LyteLoop doesn't need it all, but Harlev hopes for some of it: "Let's be honest, what's 100 petabytes between friends?"

Light storage still has one great nemesis - darkness. The light has to keep moving, topped up by a trickle of energy. Any power disruption is instantly and irrevocably fatal.

Harlev says the systems have layers of redundancy and safety features, and self-healing software. But, as we learnt in Texas and elsewhere, power cuts happen, and this approach cannot handle even a brief outage.

LyteLoop says the loss of a single system is not too concerning in itself, as the lower costs of light-based storage simply means customers would keep multiple copies in ground tubes or satellites in different locations. But it still requires a leap of faith for companies to put their data in a system that must forever keep moving, lest it dies.

Over the next five years LyteLoop hopes to bring its photonic space storage platform out of the prototype stage and into reality, making a bold bet that others will see the light.

“We believe that technology will work,” Harlev said. “So far, we have not encountered a challenge we haven't been able to overcome. But it doesn't mean that it won't happen tomorrow morning.

“We're really confident we can do this. Space is always hard, but we will get it done.”