It was early in 2001 and Kevin Moss had a job interview at the world’s most coveted corporation.

Moss (no relation to this writer), traveled up the 50 stories of Enron’s imposing headquarters in Houston, Texas, awe-struck by the success that the building represented. This, he hoped, would be where he made his fortune, a company where he could spend decades rising through the ranks.

But it would mean moving across half the country and giving up a promising career. Doubt niggling at him, he asked what would prove to be a prescient question: “I'm leaving a lot of stuff behind to come down here, are things good financially?”

Ken Rice, at the time the CEO of Enron Broadband Services, smiled. “He leaned back, popped his cowboy boots up on his desk, and proceeded to feed me the biggest line of bullshit ever,” Moss told us, two decades later. “And I bought every bit of it.”

Within a year, the company would collapse, Enron Broadband would be sold for scrap, and Ken Rice would be fighting to stay out of prison. Six years later, he would lose that fight.

When Moss attended his interview, Enron’s broadband division was part of a giant global utility company valued at $70 billion. By 2002, its value had plummeted in what was, at the time, the largest corporate bankruptcy in US history.

Enron Broadband was instrumental in causing that spectacular collapse, but it has been overshadowed by the broader corporate fraud at the energy conglomerate. The broadband business has drifted from public memory, and its role in the wider telecommunications and data center industry is little discussed.

But for those who worked at EBS, during its brief moment in the sun, many cannot forget their time there - both from the scars that the trauma of bankruptcy left on them, and from the sincere belief that they were working on something magical.

Backed by near-bottomless funding, Enron Broadband set out to dominate the nascent Internet, hiring visionaries with dreams of video-on-demand, cloud computing, and Edge networks long before the market was ready. It would fail spectacularly, but its legacy would help birth a new generation of data center companies.

We spoke to more than a dozen former Enron employees and contractors over the past four years, and they kept returning to one question: Could it have worked?

This feature appeared in Issue 50 of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

The commodification of everything

Founded by Kenneth Lay in 1985 through the merger of two smaller gas businesses, Enron began as a traditional gas and electricity enterprise supplying power across America.

Over the next few years, the company sought greater returns in riskier ventures - first by expanding into unregulated markets, and then with the “Gas Bank,” which hedged against the price risk of gas.

It was this concept, pushed by then-McKinsey consultant and eventual Enron CEO Jeff Skilling, that transformed Enron from a normal company into a rocket ship destined for an explosive end.

The company began to shift from producing energy to trading energy futures and building complex financial schemes to profit over every part of the energy sector. It would go on to trade on all types of futures, including the weather.

At the same time, Enron embraced mark-to-market accounting - in which a company counts all the potential income from a deal as revenue as soon as it is signed. For example, if Enron signed a $100 million contract over a decade, it would immediately report $100m in revenues for the quarter, even if the contract eventually fell apart.

The subjective nature of many of the deals also meant that the company would assign huge revenue numbers to contracts that could never live up to the promise.

But it meant that Enron could report higher and higher revenue figures. At least for a while.

From gas to bits

Enron fell into the broadband business. With the 1997 acquisition of utility Portland General, it also gained FirstPoint Communications, a fledging telco with a traditional business plan.

Initially, Enron expected to sell FirstPoint as soon as the acquisition closed, but Skilling saw an opportunity - to remake Enron as an Internet business. That is, at least in the eyes of investors, who were in the midst of a dot-com frenzy.

“One day, I get this phone call from a guy I knew at Enron,” Stan Hanks, who would go on to become EBS’ CTO, recalled. “He said: ‘We bought this company that’s trying to build a fiber optic network from Portland to Los Angeles, and we don't know if we should let them do it, kill it, or put lots of money into it.’”

The idea of a gas company muscling into telecoms was not without precedent - the Williams Companies were instrumental in deploying America's first fiber along disused gas pipes, developing two nationwide networks. One was sold off for a healthy profit, while the other would eventually go bankrupt (but appeared successful at the time of EBS' formation).

Talking to the Enron employees about the vast sums they were able to make trading energy, Hanks had an idea. “I just woke up in the middle of the night and said 'I can create a commodity market for bandwidth,’” he remembered.

“The guys in Houston went crazy, because the potential market size on this was enormous. They could see the ascendancy of the Internet age - they weren't sure when, but they knew it was going to happen, and they thought this would be an opportunity to gain dominance,” Hanks said.

“It looked like a license to print money, so they gave us $2 billion and said ‘Go make Enron Broadband.’”

The flaw in the machine

Every company likes to boost its stock and overpay its executives, but Enron liked to take things a little further.

Enron was already playing with fire with its mark-to-market accounting practices, using it as a way to juice its revenue numbers and puff up its stock price. It then decided to double its risk by pinning a credit line to the stock price of the company.

“That basically means that if the stock price went up, they had more money to do things with,” Hanks said “And so they now had an additional incentive to do things to pull the stock price up, which would then bring in money, which they could use to pull the stock price up a little more. But if you keep ratcheting that up over the course of time...”

The company was already, inexorably, heading for disaster, as those in charge became hooked on endlessly-growing share prices on the back of ever-greater promises. Every year, revenues needed to go up, or at least look like they were.

And, every year, Enron needed to promise something bigger.

Something bigger

These were heady times. The promise of the Internet was only just beginning to crystalize, and investors were eagerly assigning huge valuations to fledgling tech companies.

Enron was willing to spend whatever it took to be seen as one of these and was equally eager to greenlight ambitious and far-out ideas. At its height, it would value the broadband business at $40 billion, and claim that it was on track to become the Internet’s most valuable business.

Money was easy to come by. "We were splashing it around like we were rolling in it," Daryl Dunbar, the former head of engineering at EBS, said.

Those we spoke to had different tales of excess, driven both by an overall sense of opulence and an extreme focus on speed.

"The budget was almost unlimited, we were throwing money around like it was water because we had so many orders coming in and they just wanted it built as quickly as possible," a former European-based employee in charge of the Benelux colo and data center site said. "Some of the stuff we needed from the UK we would fly it in, instead of truck in, that's how desperate they were to get it built."

Another European employee remembered being flown across the continent to do simple repairs and being given access to the best equipment. "We were building everything from scratch, the requirement level was very, very high - I'm working for a cloud company right now, and our standard level doesn't go anywhere near what was requested at that time," he said.

Despite moving fast, they were also trying new things: "We were running DC currents to feed the devices,” he said. “It helps you flip faster to the battery backup system but that means that it's a lot more dangerous to connect to feed those devices. I haven't seen anyone do it since."

US-based Jim Silva agreed: “There was very little we would ever want for. Expense reports were approved without questions. Budgets to complete tasks or projects were blanket approved. It was a "get 'er done" culture and ‘how’ was not the focus, first to market was.”

By this point, Kevin Moss had accepted the job at Enron and set about trying to rein in costs. "I thought, 'Oh my god, I could be a superhero.’ It was no problem cutting costs there."

When he first traveled between his office at the Houston headquarters and another at a nearby warehouse, the company ordered him a car for the short journey. "I got out there and asked how much it cost. The guy looked at me like I was stupid for asking. It was like 150 bucks just to run me out to the office. The spending was out of control."

Before gravity caught up

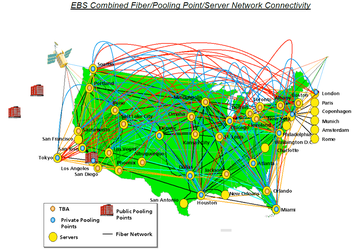

Enron Broadband began to muscle its way into becoming a major telecoms player, deploying thousands of route miles of fiber and several data centers across the United States, along with Points of Presence. Other PoPs sprung up around the world.

It funneled money into R&D, looking for ways to make the most out of the network it built. “We started a group led by Scott Yeager to create basically science fiction, developing these incredibly sexy products that ate bandwidth like crazy, that were incredibly sticky and incredibly appealing,” Hanks said.

By 1998, it was able to provide 480p streaming video over the Internet, at least to a number of US locations. “My content distribution network went live about a year before the Akamai network,” Hanks said. The company also tried to buy Akamai to complement its growing Edge portfolio, but the deal fell apart.

Several profitable, or at least potentially profitable, deals began to materialize. Enron would charge Hollywood studios thousands to send film rushes across North America when production could not wait for a FedEx shipment.

It streamed the 1999 Country Music Awards and The Drew Carey Show.

Enron also spent untold millions on Sun servers, envisioning a shared on-demand compute and storage service similar to today’s cloud computing.

As the new millennium passed, it signed a deal with one of the world’s most important tech companies. “We were going to be the broadband network underneath Microsoft’s MSN and the national network for Xbox Live,” Dunbar said. “Enron introduced a bankruptcy clause in the contract, very arrogantly saying: ‘Microsoft, you're a software company, you might blow up.’

“And then it turned out that that clause ended up going in the other direction.”

The three tribes

Already, even in the good times, cracks were showing in EBS’ shaky foundations. Fundamentally, EBS acted more like three companies than a unified whole.

There were two main sides: the Portland group that was more like a traditional telecoms business, and the Houston office led by the ‘cowboys’ chasing the next big thing. A third office in Denver tried to act as an intermediary group, although it mainly sided with Portland.

But it was Houston that called the shots.

“The Portland office was a great group,” Silva said. “A professional yet relaxed atmosphere. Houston was filled with young graduates, project managers, and folks that sort of had the ‘we'll take it from here’ approach.”

At the headquarters, they liked to throw around the phrase 'entrepreneurial spirit' to capture the bold ideas and fast pace, as well as a brutal culture that regularly laid off poor performers. Dayne Relihan, out of the Denver office, had another name for it: "Completely screwing it up."

He said: "These guys would start building stuff in the network, get out there and mess it up. I'd get a call from operations and then I'd have to send my engineers out there to figure out what the problem was and try and solve it."

One example that might symbolize the fundamental dysfunction at Enron was its flagship Nevada data center. Set to be the heart of its US operations, it was built, for no reason at all, with a sloping floor.

"The engineering people said it's got to be [Americans with Disabilities Act] compliant, but they were just talking about having a ramp in front of the facility to get wheelchairs out. They weren't talking about the main floor,” Relihan said.

“The whole thing ended up being built on a slope, so when my guys began to build all the equipment it started out at one height, but then it got to the point where the relay racks were too tall. So they had to tear it all back out again. It was an amazing comedy of errors. That's about how much knowledge they had.

“There were some really brilliant people, but they had no idea what they were doing."

Also out of the Denver office, Ron Vokoun joined Enron to help build telco sites along its network, as he had for Qwest the year before. “All those initial facilities that were in progress were all stick built, just the dumbest thing that you can do,” he said. “And then I found out that some were different.

“So we changed that and immediately started doing prefab facilities for the route from Houston to New Orleans, as we had at Qwest. We were done with that route before the one from Portland to Houston was done, even though it had been going for over a year.”

Trading places

Vokoun and Relihan were able to work around the design challenges - it was just a part of the job.

“Telecommunications is actually a pretty straightforward business, there's not a lot of magic to it,” Relihan said, noting that the core business of deploying fiber and data centers is a tried and tested model.

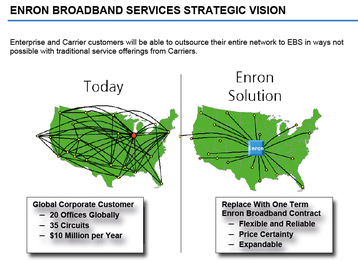

The problem, Vokoun said, was that Enron was “basically saying ‘we don't want to build or own anything anymore. We want to use everyone else's infrastructure and trade stuff.’”

Colleague David Leatherwood concurred: "There was a fabulous network, it was fiber all over the place. It's just when Enron got involved with it and decided they wanted to commoditize it all and just do trading that the end started."

For the three Enron workers, the end had truly come. “We realized they were crazy; two weeks later we left,” Vokoun said.

The idea did not seem as crazy to Hanks, who remains convinced that it could have worked. He envisioned a world where access to capacity could be traded as futures, with companies paying more during times like the release of a blockbuster movie, and less during the night.

It wasn’t ready - and even then, Enron tried to rush it. The plan had been for EBS to spin off and list on the stock market on its own, slowly developing trading while building out a network, but Enron scrapped the idea and instead moved 200 people from Enron Capital and Trade into the division to speed up the commodity market concept.

“So now we're being pulled in two directions, because the commodity market bit is not ready for prime time,” Hanks said. “It wasn't there yet. And then, all of a sudden, I've got 200 guys trying to make bills and things started getting kind of out of control.”

It got worse. In January 2000, at Enron’s analyst conference, Jeff Skilling and EBS executives “made presentations about what we were doing, and the science fiction aspect of what we had, where they managed to communicate it as though it was something that you could get today.

“Enron overrepresented what we had by a fair amount, and I decided that I really didn't want to be around for what I knew was going to be a shit show. So I ended up leaving.”

Enron cloud services

The company’s cloud efforts are one of those ideas that got overrepresented. Enron was shelling out millions for the servers, but they didn’t seem to be going anywhere.

“I was the engineering program manager, so I'm supposed to know where they went,” Relihan said. “I started inquiring about all these servers that we bought. So I fired off an email saying that I was going to do a network audit. And then the fireworks began.”

Three Houston VPs replied to the email telling him to stop the audit. “I still to this day don't know who they were or what they did, but they absolutely shut me down and said ‘No, Arthur Andersen Consulting is going to do that.’ Well, Arthur Andersen doesn't know jack shit about this stuff.”

When the fraud at Enron was eventually uncovered, Arthur Andersen would go from being one of the ‘Big Five’ accounting firms to collapsing amid the scandal - because it did nothing to stop it.

“At Enron, it was one idea after another stacked on top of another, and they were failing miserably at it because they didn't have the right people,” Relihan said.

“And they didn't want to have the right people.”

Ferraris in the fortress

Within the Houston group, there was another team nestled inside the logistics division. “We used to call it the fortress,” Vokoun said. Stuff went into a warehouse, but never came out.

Those Sun servers Relihan had tried to find were in the fortress, slowly gathering dust next to Ferraris.

“There used to be a bunch of Ken's cars over in that warehouse,” Moss said. “Two Harleys were sitting back in there, too.”

While all was not well behind the scenes, the company appeared outwardly successful - both financially and technologically. This impression would help it score what could have been its largest and most impactful project.

Instead, it would help mark its undoing.

A blockbuster deal

Seven years before Netflix began streaming films, set-top boxes were being installed in a Salt Lake City suburb. They purported to offer to residents what we now take for granted, but that was revolutionary at the time - films on demand, beamed over the Internet.

In July 2000, Enron teamed up with the largest video rental company in the world, signing a 20-year deal with Blockbuster to usher in the future of home entertainment.

“We thought, ‘Enron is delivering electricity to everyone, and they say that they have the infrastructure in place to do the same thing with video content. And we have the connections with Hollywood studios,’” said a former Blockbuster executive, who requested anonymity.

“So we got into this partnership with them - and you have to understand, Enron was the number one company in America. It was on the cover of every magazine, and they were the darling of Wall Street.”

The exec remembers constant demands to move faster, and to sign contracts with film studios immediately. “There was this intense pressure from Enron, they were pummeling us all the time: 'Where's the content? Where's the content? Where's the content?' It was ratcheting up, and we're like, ‘We told you from the beginning that this is going to take a couple of years.’”

Enron, focused more on external appearance than the actual product, would make matters worse. It announced the partnership early, against the advice of Blockbuster, before any studio deals were signed. It gave unrealistic timelines and made wild pronouncements, envisioning a billion-dollar business in a decade.

Studios were particularly concerned about digital rights management (DRM), which was still in its infancy. They were convinced that once a film was streamed over the Internet it could be copied for free.

“We had skunkworks guys, some really smart people researching how do we buffer the content into the device, keep it safe, make sure that it can't be decoded, can't be saved,” Dunbar said. “This was pretty leading-edge stuff.”

Questions also remained about the feasibility of the network to support it at scale - its Edge deployments were able to help, as were its advances in compression, but fiber still only went as far as the content delivery network (CDN).

Blockbuster originally believed that the partnership would move slowly, testing out the technology as the network grew to support it in the years to come. With the constant demands for immediate content, it became clear that that wasn’t the case.

“And so, finally, it got to the point where we said to them, ‘Look, this relationship isn't working, we need to break up,’” the exec said. “Of course, at the time, we looked like the loser company, and they were the big dog.”

For Blockbuster, the strange ordeal would be the end of its early dalliance with video streaming. “I know it sounds odd at this point, but our attention shifted over to DVD.

“Videotapes are not nearly as easy to ship, so the advent of DVD dramatically changed the whole scene for us. At that point, we didn't really recognize the threat that Netflix could become.”

The company tried to move on. “And then I got a phone call from a WSJ reporter, Rebecca Smith. She called me up and said: 'Could I ask you how much you were claiming in profit from this test?' And I replied, 'What are you talking about? There's no profit.’

“There was this silence on the phone. And then she told me that Enron had been booking profit off of it.”

For the short period the partnership, known as Project Braveheart, lasted, it managed four pilot deployments in the outskirts of Seattle, New York, Portland, and Salt Lake City. It had roughly a thousand users, and a handful of those paid a small fee.

And yet, Enron told investors that it had made $110 million.

Braveheart was a product more of financial engineering than it was a technological achievement. While it was still in the earliest stages, the company entered a joint venture with nCube, owned by Oracle-founder Larry Ellison.

In return for technology from the vendor, it gave three percent equity to nCube and the Enron-controlled investment group Thunderbird. This was the minimum necessary equity for Enron to be able to treat it as a separate entity for accounting purposes.

The venture was then sold to Hawaii 125-0, which was created by Enron Broadband with the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, with a valuation based on its projections over the 20-year Blockbuster deal. In essence, the company sold itself to itself and booked it as revenue, and then hid any losses.

EBS CFO Kevin Howard and senior accounting director Michael Krautz would later be charged with fraud for the scheme, but it took a while before the full scale of the problem was uncovered.

It would soon become clear that Braveheart was far from the only dodgy shell corporation.

The wheels come off

In February 2001, Kenneth Lay stepped down as CEO, with Jeff Skilling taking the top spot. He lasted six months in the role, before abruptly resigning, spooking investors.

At the same time, executives were struggling to hide mounting disasters. Enron Broadband reported losses of $102 million. Growing cost overruns at a delayed power plant in India (that Enron had already booked profits for) were making debt harder to shift.

Journalists like Smith and Bethany McLean began asking questions, and analysts finally began updating their glowing reports with notes about growing debt piles.

Enron employee Sherron Watkins wrote an anonymous memo to Lay after Skilling's departure laying out a number of possible accounting scandals that she had uncovered.

When contracts signed with mark-to-market failed, Enron had to then report it as a loss, but it didn’t want to reveal how many of its deals had fallen apart. So it hid the debts in shell companies, offshore bank accounts, and complex schemes that included temporarily selling assets to co-conspirators to get through a quarter. But the jig was finally up.

The company's share price began to dip, putting pressure on a business model that only worked if the price went up. Enron then announced it was going to post a $638m loss for the third quarter and take a $1.2bn reduction in shareholder equity. Compounding matters, the SEC announced that it was opening an investigation.

As more stories on the scale of the fraud began to come out, Enron stock entered freefall. On December 2, 2001, Enron filed for bankruptcy.

World’s best BOS

Unpicking the fraud from the failure is a difficult task. Some projects started with the best intentions, but failed, with the fraud only coming in later to cover up losses. Others may have been flawed from the start, with executives knowing they were destined for failure but simply not caring.

US prosecutors would spend countless hours trying to understand on which side of the dividing line to place Enron’s Broadband Operating System (BOS).

"A year after I left, I got a call from the FBI," Relihan said. "They were focused on the Broadband Operating System and if it actually worked because that was the thing they were looking at as the pump and dump on the stock."

Relihan came into the Denver FBI office to meet the Assistant US Attorney. "At one point I said 'Do I need an attorney?' and he just looked at me across the table and said 'I don't know, do you?’ And that's when I knew I was in trouble."

But Relihan was not there because he had done anything wrong. Far from it, they were curious about his emails criticizing BOS.

The operating system had been pitched to investors as a system that could talk to and connect to every part of the network through a single platform. "That was just never going to happen, because the only way that would work is if every service provider in the country allowed us access into their network management systems," Relihan said.

"It has to be able to speak every language that you can possibly imagine, because there's not an operating system out there that can talk machine language to transport equipment, fax, router, servers, and everything else."

He told this to the investigator, "and he goes 'so that was a fraudulent statement?' And I said: 'Oh, most definitely.'"

Vokoun concurred: "It all sounds great if you're not an engineer and you don't realize that crap can't actually be done that way."

The stink around BOS and Braveheart has led many to write off the whole broadband division as a con.

"There was a government case that alleged Broadband as a whole was a fraudulent company that didn't work," Dunbar said.

“I'll put my hand up, especially as the head of engineering, and say, ‘No, it really did work.’ It got caught in the mess and some of its assets were sold to special purpose vehicles, bought back, sold back again multiple times over, and fraud was committed on top of these assets. But Broadband worked.”

I gotta get out of Houston

The rapid collapse of Enron hit people differently. The sudden change of fortune was hard to process.

“They went floor by floor and called everybody down to one end of the room and said ‘You've got 10 minutes to get your stuff and get out,’” Moss said.

“I took a break and went downstairs to clear my head and it looked like a rock concert there. People were coming out of that building crying, oh my god, it was horrible. And then all of a sudden, the cameras start showing up.”

The implosion became the biggest story in the world, but most focused on the villains of the story, on the greed and the lack of regulatory oversight.

For the thousands of workers without a job, a more pressing question was how to survive.

"4,000 people losing their job in one day, suddenly the real estate market collapses in Houston," Dunbar said. "I couldn't sell my house."

He added: "It crushed my career for about four years.”

Moss had a similar experience: "I ended up having to sell my house for less than what I owed just to get out of there, because I figured, man, I gotta get out of Houston."

Making matters worse, the company had encouraged employees to convert their pensions to Enron stock. Every year, as its share price soared, more bought in. When the valuation soured, they were left with nothing.

This long after the fact, most of the people we spoke to for this piece are looking back at the start or the middle of their careers. Many were able to get back on track after a few years, and slowly rebuild their lives.

But the company’s older employees, many of whom have since passed away, were not so fortunate. Those we spoke to knew colleagues who lost everything and were unable to recover. At least one turned to suicide.

Those left suddenly looking for jobs were forced to compete with colleagues amid a difficult job market. The bursting of the dot-com bubble a year before had investors cautious of backing Internet startups, the September 11 terrorist attacks unsettled markets, and the wider telco sector was going through its own downturn.

After a flurry of over-investment, dozens of debt-laden telecommunications companies began declaring bankruptcy, with around $2 trillion wiped off the market. About 450,000 telco jobs were lost around the world in 2001, and the industry saw years of consolidation as it pulled itself out of a hole.

From the ashes

But Enron did not disappear overnight. As investigators scoured through company documents looking to uncover the scale of the fraud, others were tasked with salvaging some value out of the carnage.

“We had people lined up doing auctions for all this equipment and vehicles and all that stuff,” Moss said. “It was all going for five cents on the dollar.”

PoPs around the world were picked clean, a European-based worker said. When it became clear that staff weren’t going to be paid, equipment disappeared.

"We sold off what we could," Hanks recalled. "My DC and Network Operations Center in Portland wound up going to Integra Telecom, and they're still running their network off of that today.”

Fiber routes were sold off piecemeal, and a fiber swap deal with Qwest was unwound (the deal was itself subject to investigation as the companies had both recorded the deal as a profit).

Hanks also launched an unsuccessful bid to raise money to buy as much of the bones of the business as he could. Even now, there’s still Enron Broadband fiber out there, unlit.

“There’s almost 3,000 route miles of fiber across the American West that is just sitting there that no one is using or can use because it’s still wrapped up with the various counties and operator tax authorities,” Hanks said.

But perhaps the biggest asset to be sold, and the one that remains the most impactful today, was Enron’s data center in Nevada. Designed with some 27 carrier connections, it became the first data center operated by Switch.

Switch declined to comment for the piece, but in a tour of the data center last year an employee told DCD the company’s foundational story: “[CEO] Rob Roy turned up to the auction for the Enron data center and put in a low bid. They called him up later saying he was the only person to bid, so he retracted the offer and resubmitted one that was even lower.”

Dunbar remembers it slightly differently, without the added drama of the double bid, but confirmed that the facility was sold for a fraction of its value. “I was the guy that sold it to Rob.”

Dunbar said: "He was really smart to see the opportunity and how overbuilt that data center actually was.” A facility that cost millions and took years to build was sold for just $930,000.

'The Core' campus, as it is now known, has changed dramatically since the acquisition in 2002. The site is unrecognizable from the original facility and is expected to support 495MW of IT load after its latest upgrade. But its location owes everything to Enron.

That early win allowed Rob Roy to break into the sector for a fraction of the usual price, which he then used to build a huge data center empire. In late 2022, Switch was sold to DigitalBridge and IFM for $11 billion.

Over a few years, all that was left of Enron Broadband that could be sold was flogged off. “It was pathetic compared to what we thought the valuation of Broadband was,” Dunbar said. “We sold it for tens of millions.”

Those we spoke to discussed another EBS legacy that is harder to quantify than buildings, fiber, and dollars: connections. Many would go on to work together, start businesses, and keep some of the ideas that they formulated at the company alive over the years to come.

The bankruptcy brought those who lived through it together, and their work would help shape the digital infrastructure industry as it came out of the dark days of the early 2000s.

What could have been

For all its failures and the systemic corruption at the core of Enron, most of those former employees were convinced that EBS could have worked.

"Every build I did made money,” Hanks said proudly. “We deployed 144-fiber cables with one extra conduit, and we only kept 12 fibers. We sold the rest to other people to pay for the cost of everything else we were doing. We made an enormous amount of money off of the construction phase.

“When I left, we were really close to some major contracts with CBS. If things had not gone sideways, I believe we would have had the contract for the 2003 Super Bowl.”

He added: “All we needed was time, and that's the one thing we didn't have.”

Hanks takes solace in one of the things that time has provided - proof that at least some of the ideas were correct. “This is the future we saw, this is where we were going. So my horse was shot and rendered into glue, but we got here, by God, and so I take a lot of joy in that.”

It’s impossible to know whether there was a contract, a merger, or an idea that could have helped Enron Broadband survive.

Fraud was at the heart of the business, it was not just an unrelated activity that helped fund the company. Juicing the share price was the business, and it required constantly feeding the market new, ever more outlandish, ideas, and using accounting trickery to assign revenue to them.

Perhaps the version of Enron Broadband that was capable of bold visions and aggressive business moves was only able to exist because the pressure was on ideation and not execution.

“It seemed like they were just a big hype machine,” Vokoun said. “Someone's got an idea, let's hype it up, prop up the share price.”

Here we go again

The rise and fall of Enron Broadband is a story of an industry gripped by delusions, a company with a business model based purely around enticing investors instead of making a profit, and unproven and impossible technologies sold on a dream. It is not a unique tale.

Former Enron employees can’t help but see parallels between their time at the turn of the century and this age of AI.

The base infrastructure of artificial intelligence has value, just like Enron’s network in its day; and the overall trend of the market may prove correct, just as telecoms and data center businesses have thrived since the fall of Enron.

But the mania in the market, the hyperbole gripping every company announcement, and the speed at which everyone must move echo the chaos that led to the telco winter.

Those who lived through it are left wondering not if the next Enron is being built right now, but rather when it will collapse.

“I was talking to [a friend working in the AI sector], and it was very, very reminiscent of the telecoms boom that was going on in the late ‘90s and early 2000s,” Relihan said.

“It’s going to settle down to three or four players at the end of the day, but there's going to be a lot of stuff going on until that point where people are going to make a lot of money, some that are doing fraudulent stuff, and some that will get caught.

“It's like, ‘Okay, here we go again.’”