A data center powered by burning natural gas might not seem a very environmentally friendly thing to do. But at least three companies are doing just this, and they claim that their schemes reduce emissions.

In the US, Crusoe Energy already has 40 data centers powered by burning natural gas.

In Norway, a start-up with the unwieldy name of Earth Wind & Power has been launched with a plan to offer data processing located on North Sea oil platforms.

And meanwhile, Toronto-based Validus Power is offering a post-apocalyptic version of the concept, with mobile Bitcoin mining data centers in articulated trucks, parked at flaring oil wells, where they feed on burning gas and turn it into cryptocurrency.

If that doesn’t already sound scary, Validus calls this the Mad Maxx Mobile Power Fleet

This article appeared in our Grid Scale Supplement. Read the whole thing here

Stranded assets

All these offerings - and their environmental claims - are based on the fact that a lot of natural gas goes to waste. Oil wells produce gas as well as oil, but can’t always harvest the gas. Instead through so-called “production flaring,” unwanted gas is simply burnt off.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says it's a big problem, with oil producers burning off 142 billion cubic meters of natural gas in 2020 - roughly as much as the entire natural gas demand of Central and South America. The chief offenders are Russia, Iraq, Iran, the US, and Algeria.

Flaring contributes to the greenhouse effect, putting some 265 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere in 2020, along with eight million tons of methane, as well as other greenhouse gases (GHGs), soot, and carcinogens.

The IEA's Net Zero by 2050 scenario requires a complete end to non-emergency production gas flaring by 2030. Instead of flaring, it suggests that oil companies could use the gas for onsite power, pipe it elsewhere for use (though this needs more infrastructure), or pump it back underground to re-pressurize the oil well.

Burning for the planet

All three offerings put containerized data centers at oil rigs and oil wells. The kind of data they process, and the customers they can serve, depend on their reliability and network bandwidth.

Crusoe Energy is the farthest advanced, with 40 flare-powered data centers in action across North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado, at wells operated by companies including Devon Energy, Kraken Oil & Gas, and Enerplus.

In April, Crusoe raised $128 million in Series B funding to commercialize the service, launching it under the brand Digital Flare Mitigation. The energy will be used to run computing on Island Cloud, an Nvidia-powered GPU-centric hardware platform.

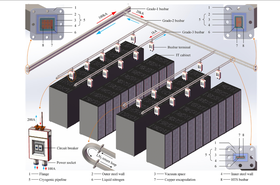

Crusoe’s Flare Mitigation data centers are modular steel structures with security access controls, dust-proof vestibules, redundant HVAC cooling, and fire suppression systems. Customers pay for power at flat monthly rates, and can have a power at 12.5kW-25kW per rack, or 250kW per module.

With multiple containers, the service can scale up to megawatts. The system has a dual-feed design with an uninterruptible power supply (UPS).

Crusoe offers connectivity to anywhere on the public Internet, at rates from 1Gbps to 100Gbps, with a round-trip latency of less than 60ms to anywhere on the US continent, 160ms to Europe, and 180ms to Asia.

“Customers are never far from their data, leveraging extensive connectivity through a high-availability, high-bandwidth fiber optic network with microwave backup,” explained a Crusoe spokesperson. “This network, operated by Crusoe, delivers 99.95 percent service availability.”

Crusoe’s current data centers are made by custom fabricator Easter-Owens, but other partners could be used in future.

Norway’s Earth Wind & Power (EW&P) is not so advanced. The company, led by Ingvil Smines Tybring-Gjedde, a former Minister of National Public Security and Deputy Minister of Petroleum and Energy in the Norwegian Government, was founded early in 2021.

Although EW&P says it aims to harness power wasted at all sorts of sites, including solar farms and wind farms, it’s clearly most focused on the oil industry, and has strong links with executives who harnessed Norway’s North Sea Oil boom.

EW&P is funded by PetroNor executives Knut Søvold and Gerhard Ludvigsen, but also has backing from Valinor Energy Group, and board members from Equinor, AGR, and renewable firms SustainSolar and Norsk Vind.

EW&P has ordered a 1.8MW high performance computing (HPC) data center container from Germany’s Cloud & Heat, a company with a history of using liquid cooling to reuse waste heat from data centers.

The 40 ft Cloud & Heat module contains 144 water-cooled servers, and can be used in temperatures between -30°C and +48°C. It will be delivered in the second quarter of 2022. EW&P hasn’t said where it will go, but the company announced a pilot project with Rapid Oil Production in September.

Rapid Oil Production and EW&P will conduct a three-month feasibility study of power-to-data-center projects off-shore in the North Sea, with Rapid installing Cloud &Heat’s containerized data centers on Rapid’s Fyne Field oil rigs in the North Sea.

“Off-shore North Sea is a key market for us given the scale of the opportunity,” commented EW&P CEO Tybring-Gjedde at the announcement. “We look forward to working with RPO and other innovative companies which share our goal of further reducing emissions as we transition to a net-zero world.”

Toronto-based Validus says it has been operating its mobile Bitcoin mines for the last five years, across many different industries with excess energy.

“With this system, we can generate a profit while eliminating harmful greenhouse gases,” says Validus. “This technology can be deployed rapidly, anywhere, at scale and remain fixed for decades or redeployed within 24 hours notice.”

How does this help?

But how can burning gas reduce emissions? All the providers claim that using flares for data processing actually reduces total emissions, because gas is burnt more efficiently in a generator, converting more of the methane to carbon dioxide.

Crusoe, for instance, claims that its mitigation service reduces methane emissions by around 98 percent, and this reduces CO2-equivalent emissions of greenhouse gases by 63 percent. This is based on the fact that methane is 80 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas.

EW&P also told DCD that harnessing the gas will ensure a fuller combustion, so less methane will be emitted.

Take that with a pinch of salt, though. Methane is much less stable than CO2. It only lingers in the atmosphere for 12 years before breaking down to CO2 and water, while CO2 remains for centuries.

The providers also state that the data centers do not enable any new oil exploitation. Nicolas Roehrs, CEO of EW&P’s partner Cloud & Heat told DCD: "It's not intended to create new oil and gas sites. We, and especially EW&P, are offering a way for existing oil and gas fields to reduce their carbon footprint and to decarbonize the complete production process in this industry."

Who are the customers?

There’s one more big question to ask, however. What are these data centers doing? The best solution for the planet would probably be to pipe the gas elsewhere, or else generate electricity and use it to create green hydrogen.

Instead, many of these remote data centers will be used for cryptocurrency mining, an activity with little benefit, whose impact on the planet is already widely criticized.

Bitcoin mining takes cheap electricity and uses it to produce cryptocurrency, a speculative asset with no inherent value or links to real assets. The blockchain technology behind it is explicitly designed not to be scalable, and each Bitcoin transaction uses an increasing amount of computational power.

Estimates of Bitcoin's power use vary, but it’s reckoned to consume as much electricity as Argentina.

Validus’ Mad Maxx, with trucks rolling up to suck on burning gas flares, is exclusively designed for Bitcoin: “There are two industries that have garnered a bad reputation due to their carbon footprint or consumption of energy: oil producers and Bitcoin mining,” the company says. “But what if we could use the undesirable carbon output from oil producers and provide low-cost energy for Bitcoin mining?”

Mad Maxx’s Bitcoin mining rigs don’t offer high bandwidth connections or massive reliability, but Bitcoin customers don’t care about normal data center service issues. They simply want to burn as much power as possible, as fast as possible, in the race to solve the math which generates new coins.

Norway’s EW&P is more cagey about the intended customers for its eventual service, but has pretty clear links with Bitcoin mining. The Cloud&Heat container data center it uses was co-designed by Bitcoin mining company BitFury, and EW&P’s website contains some very positive material about Bitcoin mining.

EW&P's "Fact Center" quotes a prediction from Fortune Business Insights that blockchain will reach $69 billion by 2027, and one from Gartner that it will generate $3 trillion by 2030, and may be running 20 percent of the global economic infrastructure by then (an unlikely prediction, considering how much energy would be needed to run 20 percent of the world’s economic infrastructure on the inefficient blockchain network).

EW&P seems to have moved away from the mining emphasis in a more recent downloadable brochure, which lists several other applications such as 3D rendering, simulation, and image processing, all of which can be done at remote sites - but only if there is a good data connection and the power is not too intermittent.

For Cloud & Heat’s Roehrs, it seems that Bitcoin is just a step on the way to creating useful computing, by enabling that feasibility study: “The final goal will be to implement and setup HPC sites,” he told DCD. “Since this is the first container DC we will start with some blockchain applications.”

Real value

Compared to these two, Crusoe is reaching a more varied portfolio of customers. Existing users include Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (MIT-CSAIL), Folding@Home, and OpenCV, a library of computer vision tools.

Thanks to its strong networking and reliable service, Crusoe is able to serve “a wide range of Cloud Computing applications”, a spokesperson told DCD, explaining that services which only have basic satellite connectivity are limited to crypto mining.

“We provide pure data center services and cloud computing,” said the spokesperson. “Crusoe Cloud can offer high-performance GPU-based computing power with low latency, reliable networking, high-speed data transfer and a carbon-negative emissions footprint at low costs. This has applications across Deep Learning, 3D Rendering, Computer Vision, Scientific Modelling and more.”

Perhaps gas flares are more than hot air after all.