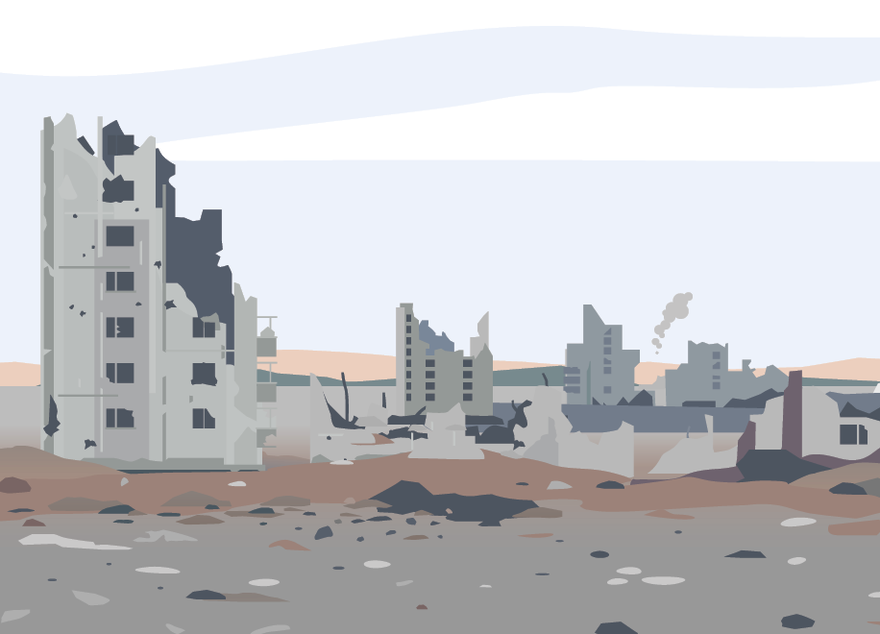

In a year where arctic forests burn, cities experience their first major floods, and record hurricanes batter unprotected towns, belief in a stable world is perhaps a sign of an unstable mind.

Our planet is becoming an increasingly dangerous place, threatening not just people’s lives, but the buildings that support societies, and the grid that powers it all. And yet, despite copious evidence showing these rising risks, many are continuing to operate with a business-as-usual mentality.

“It's incredible to me to see that even data center operators are not considering that at all,” Ibbi Almufti, head of the risk and resilience practice at global design and consulting firm Arup, told DCD.

“They're just building like everyone else builds - it's crazy.”

This feature appeared in our special colo design supplement. Subscribe for free today.

Facing reality

Data centers are often designed simply to comply with modern building code standards, which on the face of it seem to be written to ensure the construction can withstand a reasonable amount of disaster. “But the only thing the [building codes] care about is life safety. And even when you're designing to a higher level of code performance, it's just lower life safety risk.

“It's never looking at functionality-level performance or anything like that,” Almufti said. Considering the rising perils, and the need to maintain data center uptime, data center design needs to “move the goalposts from life safety to beyond life safety and look at limiting downtime and repair costs and protecting your investment.”

He added: “I will venture to say that if you're building data centers right now, in higher natural hazard zones, you most likely will not be meeting your availability targets even if you're designing to modern building codes.”

It’s a question of weighing the cost of making a data center more resilient versus the benefit of it not suffering downtime - or, at least, returning to service faster. “With data centers, if you're out for a day or two, you're out millions of dollars,” Almufti said. “You could just take those millions of dollars and invest it up front to prevent that from happening in the first place. Kind of a no brainer.”

Anthropogenic climate change has made the weather more savage and unpredictable, and will soon make it much worse. But it’s not the only problem.

“Forget about global warming for a second, if you have a site you built 10 years ago, and now you've got land being developed [nearby], then all of a sudden, you’ve got water run-on - that's increasing your flood hazard,” Almufti said.

In the Midwest of the US, as well as elsewhere around the world, “there's new seismicity from the deep well wastewater injection,” also known as fracking. “This is man-made induced seismicity,” Almufti said. “And scientists discover new faults all the time - I'm a seismic engineer - you will never see the seismic hazard go down in a location because of new science, it always goes up.“

Those looking to design for seismic events could learn from Japan, a nation that has wrestled with earthquake after earthquake.

After opening a new data center in the country in 2017, Colt DCS' VP of operations, Ian Dixon, told DCD: "The tried and trusted way to make a structure more resistant to the lateral forces of an earthquake is to tie the walls, floor, roof together to form a super-structure. Then have an isolated foundation that becomes the sub-structure.

“That is the basic premise for our latest data center. However, in order to nullify the vibrations and keep the equipment as safe as the human inhabitants, we also needed to look at what the building sits on.”

Colt’s Inzai 2 facility sits on a series of seismic isolators and Teflon sliders. “These isolators are sometimes called a Shake Table - capable of holding 125 tons per m2, isolating the whole building from any seismic forces and allowing the sub-structure and super-structure to move independently,” Dixon said. “Thus, permitting the bulk of the seismic shock/energy to be dissipated by the sub-structure and reduce the impact on the super-structure."

That might be excessive for most US data centers, but the problem is that the majority of data center operators may no longer be aware of the risks surrounding their facility, and what design changes they need to make.

It's only getting worse

Worsening weather, flood runoff risks, seismic changes - “a lot of these things just slip through the cracks,” Almufti said. “You might have assessed the risk at one point - probably not - but even if you have, it's changed a lot in the last 5, 10 or so years.”

Even when a facility itself is protected from these changes, it may be at the mercy of surrounding infrastructural weaknesses. “Our analysis shows that relatively low wind speeds can cause power outages. This is primarily due to trees falling on power lines and disrupting the services - they're typically down for one, two days at a time. It's not an infrequent event.”

Another problem “is that multiple data centers may be relying on the same utility substation, and that substation is essentially a single point of failure,” Almufti said. “A lot of the substations that we've seen are in flood zones, for example.”

That’s why some are turning to microgrids to give data centers more control over the power used to keep their data centers online.

"We know that gas can go down, we know that power can go down; it's about making the site secure," Arup associate Russell Carr told DCD.

Microgrids incorporate three key components: “You've got some generation, you've got some storage, and you've got a demand or load,” Carr said. “Generation can be provided by multiple sources - it can be variable renewables, such as photovoltaics, wind, biogas fuel cells, natural gas fuel cells, natural gas generators, regular generators - it just needs a system to provide power but it has to have storage as well, that can be lithium-ion batteries, flow batteries, various technologies.”

The decision over which generation and storage technologies to use is dictated by the hazards found in the data center’s location, as well as local regulatory stipulations.

“Let's say I'm on the East Coast [of the US],” Carr said. “There’s a lot of overhead power lines, I might have my backup generation in gas fuel cells because I know in Superstorm Sandy the gas system stayed up, while the electricity system stayed down.

“Whereas, on the West Coast, the disaster here is an earthquake, gas lines can go out for a long time, but electricity would typically be restored back in a week.’” Regulations, such as air quality laws in California, dictate design: “Diesel generators can't operate all the time, gas turbines go through a lot of permitting because California is trying to phase out gas… these are things you have to consider.”

Arup recently completed a microgrid project in California for a confidential client who wanted to build a multipurpose campus with several Edge data centers. “Resiliency was a big driver for this site,” Carr said. “The client's aim was to be able to operate indefinitely independent of the grid for their key loads,” islanding the site off from the wider grid.

“This client wasn't stupid, they didn't want to put this in for free - they also wanted the system to make money, so we looked at how can we make money [from] the battery capacity of this site.”

For the campus, the client had 4MW of Edge data center load in each of the four buildings, along with around 20MW of general campus load. “We had 16MW of solar on site, 6MW of diesel generation, 4MW of fuel cell generation, and 5MW of batteries at this site,” Carr said.

Should clouds gather over its solar panels, the system proactively drops non-critical loads before the shade cuts photovoltaic output. Whatever happens to the outside world, the campus can continue on, an island unto itself.

But, Carr conceded, such luxurious grid resilience is only really for smaller data center deployments: “If we're looking at a big hyperscale data center, it's harder to put renewable generation on that data center - even if you covered the roof with solar, it's a 100MW data center. You're gonna power the lights.

“You've got to look at the load of that particular building and the size of that building, and how to match up generation and storage to that building.”

Microgrids for larger facilities can still provide financial returns, and help improve grid resilience, but full islanding is unlikely. Instead, with such sites, it helps that the companies that operate those data centers usually manage numerous facilities.

“It’s about basically combining the interdependencies of those data centers,” Almufti said. “So, for example, the parent-child relationships between individual data centers and comparing that against the spatial extent of a given hazard scenario to understand the likelihood of simultaneous outage and downtime at multiple data centers.”

Such an approach can “inform ideal separation distances between existing data centers and new data centers.”

Despite such precautions, no matter how much one prepares, no matter how strong one builds, there are still the unknown, unpredictable dangers. “A major solar flare could wipe out the entire eastern seaboard,” Almufti said. “Things would be down for months - everything, not just the individual data centers. Solar flares are kind of scary, I don't think we can quantify the risk to that. That's like a black swan event, but it happened 250 years ago, so it's possible.”

There are several such hazards where “the cost benefit would show that you shouldn't design for these events, if you're not impacted for hundreds and hundreds of years.

“One thing that's lurking out there is the New Madrid Fault Line in the Memphis area. That fault ruptures every multiple thousand years, but when it does, it's huge. So how do you design for that?”

And, with some risks potentially wiping out the region’s population, is there even any point designing for that? Such questions can weigh on someone, and Almufti admits that immersing himself in a world of risks has changed him.

“I'm super risk averse,” he said. “I live in San Francisco, and when I walk through downtown I’m always looking up like 'Oh my god, please don't happen now,' or if I go in an older building, it’s like ‘get me out of here right now.’

“It's kind of like living in like The Matrix - no one else sees it, but you see it because you do it every day. The chances that you're in a building when the disaster strikes is really low, but it happens.

"It happens.”