In most industries, the kind of surge in demand provoked by interest in AI-based applications would be a cause for celebration. But in the data center sector, the demands for decarbonization, combined with power supply rationing by utilities – not to mention ever-more onerous regulatory demands targeting data centers – means that the champagne will have to remain on ice until these challenges are overcome.

After all, a data center can’t even be built without a guaranteed supply, and in places as far-flung as Singapore, Dublin, San Francisco, and London the waiting list can be years, without any guarantee that it will be delivered as promised. Moreover, in popular locations in places like Germany and the UK, commercial power prices are also among the highest in the world.

So, instead of quaffing champagne, data center operators will no doubt need to take something for their headaches.

“We talk to a wide variety of operators. The problem is global. They’re in Singapore, Hong Kong, London and Frankfurt. All those areas are experiencing utility limitations in terms of the power that could potentially be assigned to data centers in high-density urban areas.

“They’re being told that they may not be getting any more generating capacity from the utility and they’ve got to figure out a way to supplement what they’ve already got if they’re going to continue growing,” says Peter Panfil, vice president of Global Power at Vertiv.

“So the local utility says that they won’t have any additional power generating capacity for, maybe, five or ten years. What do those data center operators do when they have customers that want to deploy high-performance compute AI loads today?” he asks.

Data center operators are also facing increasing restrictions on the usage of diesel backup, so these can’t simply be switched on at peak times to supplement a lack of available grid power while gas turbines are not looked upon any more favorably by the authorities responsible for local permitting, either.

“If I want to bring my own power and run a continuous diesel or natural gas turbine genset, local jurisdictions are increasingly saying ‘no’. There was a very notable rejection in Northern Virginia recently where a data center operator tried to get permitting for three-megawatt diesel generators – to cover 300MW of grid supply.

“So if the utility power failed they would have all 300MW of those generators come online at the same time, with all the noise and emissions that would entail. There has to be a better solution,” says Panfil.

Bring your own power

Inevitably, the solution points in the direction of microgrids, although many data center operators – whose facilities are already complicated enough as it is – may initially recoil.

“People have the wrong idea about microgrids,” says Panfil. “But, quite simply, microgrids are just connected distributed energy resources. Data center operators that already have a UPS and generators are already running a form of microgrid. The only difference is that those microgrids are reactive,” says Panfil. That is to say, they typically only kick in when primary power goes down.

But how can you build a microgrid if diesel engines can’t be used and gas is next in regulators’ sights? Panfil suggests that a combination of more powerful batteries and new developments in fuel cell technology will provide the answer, and many Vertiv customers have already started this leg of their journey toward both power self-sufficiency and net zero.

“They’re examining their outages and their durations, and are asking, ‘What can I solve with long-duration battery storage?’ So they’re mapping their outages and seeing that they can solve 25, 50, or even 75 percent of their outages with just a longer duration battery.

“We’re seeing customers taking these first steps, adding further battery storage or a battery energy storage system (BESS). That means that, once established, they don’t have to trigger their generators the moment there’s a utility failure. They can hold off starting them up until absolutely necessary,” says Panfil.

A BESS, such as Vertiv DynaFlex, is a standalone long-duration battery that can be deployed at either the medium-voltage or low-voltage point where the facility would normally connect with the utility; typically, where the backup generators are connected today, according to Panfil. DynaFlex is scalable from 250kW to 100MW.

While data center operators may initially be nervous about shifting to this model Panfil believes that, in time, they will become more comfortable with it, while battery technology is only going to get better, making this approach more and more compelling.

This will enable users in facilities with aggressive local regulations on the use of diesel backup engines to reduce the number of days they need to deploy them, with a view to phasing them out entirely in the foreseeable future.

Going hybrid

A BESS may provide a data center operator with more flexibility while conforming to ever-more rigorous regulations on emissions but, at some point, it will need to generate more power on-site to supplement power provided by the utility. And if gas and diesel are out of the question, what is available that can fill the gap?

Panfil believes that hydrogen fuel cells hold the key; initially running on natural gas but soon, on hydrogen piped/, or stored on-site as the hydrogen economy takes off. Initially, the fuel cells will take the place of the diesel or gas backup engines but, over time, could provide a greater share of the facility’s primary power.

Natural gas fuel cell technology is available now, and offers a mature production and distribution infrastructure, generating relatively clean electricity, albeit with some greenhouse gas emissions.

Pure hydrogen fuel cells, meanwhile, are only now on the cusp of widespread adoption, although hydrogen-ready natural gas-powered fuel cells are becoming available so that users can make the switch at the appropriate time.

Analysts at Dell’Oro Group suggest that the characteristics of proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells will be most appropriate for backup applications because of their ability to start up quickly, while solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFC) are best suited to provide continuous power and can use either natural gas or pure hydrogen, providing future-proofing for early adopters.

However, fuel cell technology also needs to be supported by batteries with high cycle capability, because they can be relatively slow to respond to load changes and therefore need a way to make up the gap.

“By configuring the fuel cells and the UPS system in parallel, the fuel cells can dissipate excess energy resulting from load changes by storing energy in the battery system,” notes Dell’Oro. The data center operator, meanwhile, can profit by offering surplus power captured by its BESS back to the utility in the form of grid-balancing services.

While it might be hard to foresee how the sustainable production, transport, and storage of hydrogen will take off, it’s worth bearing in mind that it took decades for the fossil fuel infrastructure behind the road transport revolution of the 20th century to develop. The development of the hydrogen economy is set to be considerably quicker.

“Different transport mechanisms and storage mechanisms will evolve. In a recent proof-of-concept project, we contacted an H2 provider. They showed up with two trucks with the appropriate plumbing built in, and the H2 stored in them. These trucks would enable the fuel cells to be run at a megawatt for about 24 hours,” says Panfil.

It might seem like a big step to take today, but the data center of tomorrow could enjoy greater security and flexibility under a microgrid model in which fuel cells are not only able to provide backup power, but primary power too – overcoming that triple whammy in the process.

For more information about Vertiv Trinergy, visit the product page or explore its campaign.

More from Vertiv Power

-

Vertiv launches Trinergy UPS system

Targeting high capacity hardware

-

Vertiv adds ZincFive’s nickel-zinc batteries to UPS offerings

Companies can choose alternative to lead-acid or lithium-ion

-

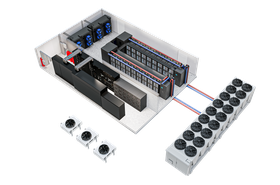

Vertiv launches high denisty prefabricated modular data center for AI

Claims to reduce digital infrastructure delivery time by 50 percent