"If it wasn’t me, it would have been somebody else,” Martin Cooper, otherwise known as Marty, tells DCD.

Except it wasn’t somebody else, it was Cooper who invented the first ever portable cell phone.

His legacy is particularly poignant this year, as it marks the 50th anniversary since Cooper made the first call from the portable device he designed.

Beginnings

Born in 1928 in Chicago to Ukrainian Jewish parents, as a child Cooper only wanted to take things apart and fix them.

“From my earliest memories, I've always known I was going to be an engineer,” he says. “I always loved to take things apart, and occasionally I actually put it back together again. I had an impulse to understand how everything works, so it was no surprise that I went to a technical high school.”

After graduating from the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), he served as a submarine officer in the Korean War.

Then his drive to do engineering took him into the mobile telecommunications world, working for the Teletype Corporation and joining Motorola in 1954.

By 1973, he was still at Motorola, leading a team of engineers working on truly portable mobile communications.

A passion for engineering

Almost a hundred years earlier, Alexander Graham Bell invented the original landline phone, but now Motorola was competing with Bell’s legacy, formally known as the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, and more commonly known today as AT&T.

At that stage, Cooper explains, the Bell System had a monopoly over telephone communications. Mobile communications were arriving, and AT&T wanted to extend that monopoly.

“If you wanted to have a telephone, you got it from the Bell System. And they announced that they had created a cellular telephone. The nature of this telephone was that instead of being connected by a wire, so that you are trapped at home, you could now have a car telephone - so you're going to be trapped in your car. I didn’t really see this as an improvement.”

While Bell had control of the carphone market in the States at the time, Cooper dreamed of untethered devices.

“Tactically, Bell said they were the only ones in the world competent to do it and therefore wanted a monopoly. And, of course, Motorola objected to that mostly because the Bell System would probably take over their businesses as well as the telephone.

“It looked like they’d be the only provider, so at that point, I decided that the only way we were going to stop them is to show what the alternative was and open up the market,” explains Cooper.

“Their view of the current telephone was that there are very few people that wanted it and that there really wasn't enough business there. But my view was that someday when you were born, you would be assigned an individual phone number.”

Taking on the competition

Cooper and Motorola were on a mission. He and his team of engineers wanted to innovate and show that phones could be portable, and the company was determined not to allow AT&T the opportunity to dominate the market.

AT&T in the 1970s had an arrogance about it, Cooper feels, as the giant dominated the telecommunications market at the time.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) looked set to grant AT&T the spectrum it would need to continue its hold, with a hearing scheduled for 1973.

Motorola and Cooper were up against the clock to prove that there were other engineers capable of making serious contributions to the telecoms market in this era.

In his mind, Motorola had to go big and deliver something “spectacular” to show the regulator an alternative.

He recalls telling Rudy Krolopp, head of Motorola’s industrial design group, to design a portable cell phone. Krolopp wasn’t too sure what one of those was, says Cooper, but saw the project as exciting and jumped on board.

The phone

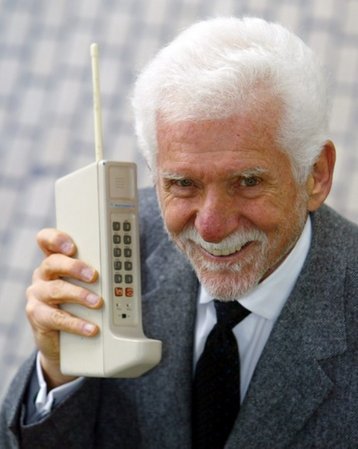

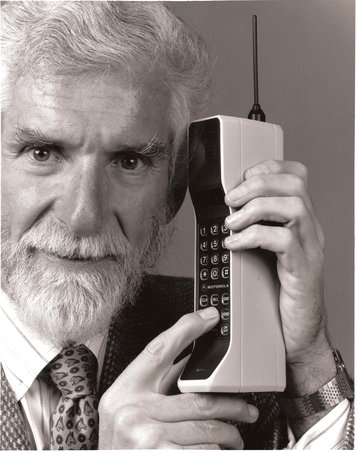

After a frantic few months, Cooper and his team put together a mobile phone, the DynaTAC (Dynamic Adaptive Total Area Coverage). It was 23cm (9 inches) tall and weighed 1.1 kg (2.5 pounds). It allowed 35 minutes of talk before its battery ran down.

That sounds paltry today, but was revolutionary for its time.

But developing a piece of technology hardware is one thing, getting people to accept it is another challenge.

So on April 3, 1973, Cooper and Motorola arranged to showcase the DynaTAC in New York City. Initially booked in to appear on CBS Morning News, the team was left disappointed when, at the last minute, the news station canceled. Instead, Cooper’s PR team set him up with a local radio station.

Cooper spoke about the importance of carrying out the phone call outside to best paint the picture for his vision - a portable phone that can be used on the move, anywhere, while live on the radio.

He met the reporter outside a Hilton hotel.

In the build-up to the call, all he could think about was if the phone would actually work.

He weighed up his options about who to call first, before deciding to dial Dr. Joel Engel, who worked at rival AT&T.

“I never thought very much about who I was going to call, but at the last minute I was inspired to call a guy that was running the Bell System Program,” says Cooper. “So I reached in my pocket and pulled up my address book, which does give you a hint of what primitive times they were, then looked up Joe's number and I called him, and remarkably he answered the phone. I said: ‘Hi, Joe. This is Marty Cooper. I'm calling you from a cell phone, but a real cell phone, a personal, portable, handheld cell phone.’”

He jokes that Engel, who viewed Motorola as an “annoyance and hindrance,” has since told him that he doesn’t remember the call.

“I guess I don't blame him. But he does not dispute that that phone call occurred,” he laughs.

The following years

Despite the breakthrough of this phone call, it was only a demonstration and not the finished article.

In fact, it would take a decade more of development before Motorola introduced the DynaTAC 8000x in 1984. Despite its price of $3,995, the phone was a success.

Later that same year, Cooper left Motorola, the company he had worked at for 30 years, to set up Cellular Business Systems, Inc. (CBSI), a company that focused on billing cellular phone services.

A few years later, Cooper and his partners sold CBSI to Cincinnati Bell for $23 million, before he founded Dyna with his wife, Arlene Harris.

Dyna served as a central organization from which they launched other companies, such as ArrayComm in 1996, which developed software for wireless systems, and GreatCall in 2006, which provided wireless service for the Jitterbug, a mobile phone with simple features aimed at the elderly market.

Legacy?

That mobile is for everyone It’s impossible to know where the mobile industry would be were it not for Cooper.

He’s pretty humble when it comes to talking about his legacy. Instead, he’d rather praise the work of his colleagues. He doesn’t believe it’s his legacy. He says the mobile phone is for everyone.

“What is my legacy? Well, people are very nice to me, but maybe that’s because I'm so old,” he jokes at 94.

“But it took a long time for people to realize the impact of the cell phone on society. There are more mobiles in the world today than there are people.

“For most people, the mobile is an extension of their personality. For us people in developed countries we often don't realize that in certain countries, the mobile is the basis of people's existence. Their very first phones were not wired phones, they were mobile phones, so we really changed the world so much that people now can’t always accept that the phone hasn’t always been there.”

Going back to the battle with AT&T to demonstrate the first mobile phone, he says that if he wasn’t successful a very different path in the industry would have been carved.

“Oh, I have no doubt in my mind that had Bell succeeded they would have built a system that was designed specifically for cars,” he states.

“If they had built a system designed specifically for cars, it would have been at least 10 or 20 years longer before we would have had portables. Because car cell phone deployments just didn’t make any sense.”

Cooper accepts that if he hadn’t invented the mobile phone, someone else would have done so. But he is understandably glad that it was him, and Motorola, that did so.

Do not fear failure

As with all creations, there are challenges, and this was something that Cooper faced a lot during his career.

The battle to prove that Motorola could provide competition to AT&T was arguably the toughest challenge of them all.

It wasn’t easy to convince the FCC that there were other options, he says, adding that Motorola had its own issues, from the direction the business was headed in, to competitive threats, internal disagreements, and regulatory policies.

Cooper admits it wasn’t always easy and that he had failures while at Motorola, but explains that the company, which was founded by Paul Galvin and his brother Joseph, provided a lot of encouragement and support.

“The wonderful part about Motorola was the motto that the founder of Motorola, Paul Galvin, instituted. His motto was, ‘Reach out, do not fear failure,’ and I took that very seriously,” he says.

“If you think about it, trying to build a portable telephone at that time, I was really sticking my neck out, and of course, the company stuck their neck out too.

“Between 1969 and 1983, Motorola spent more than $100 million - and this is back then, so they really bet the company on this idea. I was really fortunate having a company that accepted failure and I took a lot of chances and had a few failures myself, and the company tolerated me for 30 years. It was one of the luckiest things I ever did in my life.”

Source for good

While some say society is now too reliant on mobile phones, Cooper isn’t concerned.

Instead, he sees the mobile phone as a source of good, and one that can help to eliminate poverty in some parts of the world. He claims that mobile phones have helped developing countries stay connected, providing new opportunities.

“It turns out that the cell phone does a lot of things that can make us more productive and also improve our ability to distribute the wealth that we create now. So I think the most important thing short term that the mobile phone is doing is the elimination of poverty.”

As with everything, with the good comes some bad, and there are definitely some negatives around mobile phones, notably scammers and a rise of cyberbullying, though this could largely be seen as a social media problem, as opposed to a mobile phone issue.

There are also other security issues that can impact mobile phone users, which again can be found on desktops as well.

But that ties into Cooper’s other passion: education. He told DCD that he wants students at school to be educated about the mobile phone.

“I’m currently working on a committee, and one of the things that I'm suggesting is that every student has full-time access to the Internet, and the only way to do that is with a smartphone,” he says.

“But the pushback that I get is ‘no these kids are at school and they're going to be distracted.’ This doesn’t wash with me, as there have always been distractions in the past, long before mobile phones were around.”

A glimpse into the future

Although he says the industry has come a long way so far, Cooper is adamant that we’ve barely touched the surface of what mobile can offer us.

“I have to say that it's my view that we're just beginning the mobile phone revolution.”

He understands the need for 5G, 6G, and other future developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), but it’s actually the Internet of People he’s fascinated about.

This vision ties in with what he expects future smartphones to look like, where the human is very much the device, with built-in sensors. He doesn’t give a timeframe for this, but says that he expects future phones to be driven by artificial intelligence.

“At some point, and it's going to be a few generations from now, everybody will have sensors built into their body. And before you contract a disease, the sensors will sense this. There is the potential to save lives and eliminate diseases, mostly because we have people connected.”

Using AI, future mobile phones will examine our behavior, adds Cooper, noting that we should embrace “making the cell phone part of our personality and not just a piece of hardware.”

As for future form factors, it won’t be a flat piece of glass, says Cooper, but likely embedded in some way into our body.

Team effort

Concluding our conversation, Cooper was insistent that he shouldn’t get sole credit for the birth of the mobile phone.

“I didn't do this all by myself. It took hundreds of people to create the mobile industry as we know it today and, in fact, even when I conceived of the first mobile telephone, I knew that it couldn't be done alone.

“I studied all the technologies, but it took a team of really competent engineers to put that first mobile phone together. So I feel very good about the fact that I've made a contribution to this.

“But by no means am I the only person that created this.”