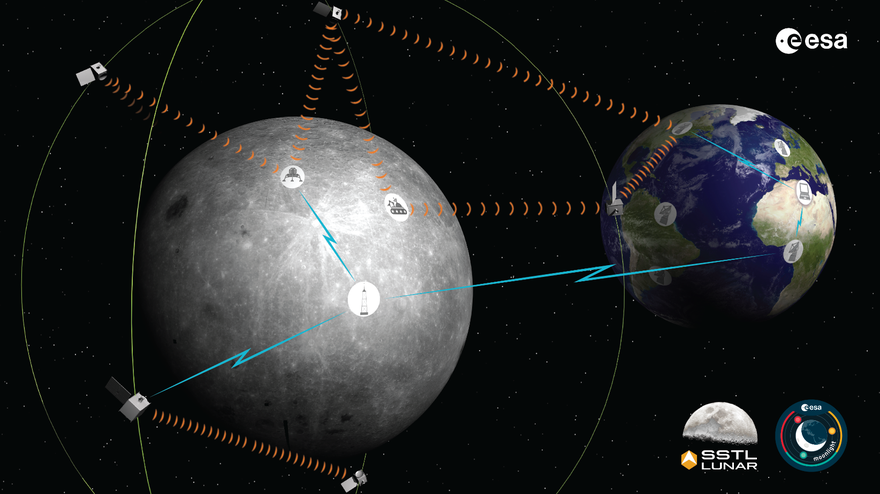

The European Space Agency plans to build a telecoms and positioning network around the Moon, with a constellation of satellites.

‘Moonlight’ hopes to speed up Lunar research efforts, lay the groundwork for human habitation, and provide the foundation for Solar System connectivity.

"I believe that in a moment of fragility for humanity, like the one we experience now, what we really need are bold and visionary targets and projects to bring humanity together to push the borders of progress and innovation," Italian Space Agency president Giorgio Saccoccia said at a virtual media event attended by DCD.

"The idea of going back to the Moon in a stable way to stay, to deploy humanity outside our planet is exactly the type of project that we need [right now]."

Moonlight hopes to form a key part of efforts to colonize the Moon, building a telecoms network that can "support any Lunar asset anywhere on the Moon or around the Moon," Phil Brownett, managing director of Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd, said.

"Our consortia is focused on building an off-planet service provider," he added.

SSTL is leading a Phase A/B1 Study into the Moon telecoms system, in collaboration with SES Techcom and Airbus.

Connectivity to Earth will be handled by Norwegian ground station Kongsberg Satellite Services and the UK's Goonhilly Earth Station, which we visited last year.

Simultaneously, a separate group led by Telespazio will study the architecture of the Lunar Communication and Navigation Services.

"In the first phase we have those two consortia that are in competition, and then eventually for the next phase, we will select either one of the two consortia or a reorganization afterwards," ESA's director of telecommunications and integrated applications Elodie Viau said.

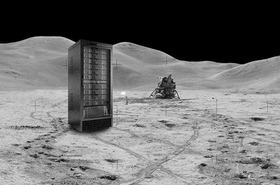

Telespazio is also working with Thales Alenia Space to evaluate Lunar infrastructure, including a data center on the Moon, which we profiled earlier this month.

"Starting to put in place infrastructure as this project is doing is really essential if we want to make the Moon into that very vibrant area of space activity," UK Space Agency head Graham Turnock explained.

"We're incredibly excited as the UK Space Agency to be supporting this, and it really is a very important day. I think in 20-30 years, we'll look back on this and say this was an absolutely critical moment in the evolution of the off-Earth space sector as we move out of Low Earth Orbit."

The navigation aspect of the project is also vitally important, ESA's director of navigation Paul Verhoef said.

"At the moment, if you want to go to the Moon, you need basically two things for navigation purposes," he added.

"You need on the Earth very large antennas which will track you and determine your position. This is very costly, there are few installations around the world that can do that, you need a number of them working at the same time, and you need hours before you have a reliable piece of information."

These antennas can only track one object and, for all that work, give an accuracy of anywhere between 500m and 5km.

"The other thing you need is on your lander is quite a piece of subsystem that can handle the navigation and positioning, measuring the height to your surface, etc.," Verhoef said, adding that it adds about 40kg (Earth weight) to every lander, as well as cost."

The hope with Moonlight is to shrink that load down to a small receiver and an altimeter - massively reducing the cost and complexity of Moon machinery, as well as opening up the side of the Moon not in direct line of sight to Earth.

It should also prove much more accurate. "With a small constellation, the target is an accuracy of 100m," Verhoef said.

"Probably better, we think we'll be able to get it to 30m in the first instance, which is what NASA has specified what they want for their future landers."

Beyond that initial deployment of three to four satellites - as well as small base stations that are used to hone positioning, more investment could allow for greater accuracy. "If we talk about a reference on Earth, with Galileo we're able to do less than 1m accuracy, we're hoping to go to 15-20cm in the coming years."

Before the satellites, Galileo - and rival positioning systems GPS, BeiDou, and GLONASS - will help with Lunar positioning as an intermediary steps.

"The signals [from these systems] go to the Earth, but they also bypass the Earth and go further into space," Verhoef said. "We can combine the use of those signals into a receiver in order to determine position."

This GNSS receiver will first be tested on the Lunar Pathfinder, a data relay satellite that will open up the polar and far-side to connected missions from 2024.

”The Moon is a cornerstone of ESA’s exploration strategy,” says David Parker, ESA’s director of human and robotic exploration, “this decade we will see humans and robots visit uncharted territory and return with new discoveries, communications is key to send scientific and operational data to Earth.”

At the same time as Pathfinder gets ready for launch, the wider Moonlight studies will continue - with this early evaluation expected to take between 12 and 18 months, following smaller studies over the past two years.

"And then the idea is that this could be one of the projects that we take to the ESA Council of Ministers in 2022, to propose for implementation," Parker said.

Pathfinder is just a single technology demonstrator satellite capable of supporting small robotic landers, he said, with Moonlight needed for wider human exploration.

"This is real, this is happening," ESA's Viau added. "Connectivity is the backbone of the exploration of space," she said.

"With the potential that we have heard of landing anywhere on the Moon, there is a full landscape of possibilities that one can imagine now. A radio astronomer could set up observatories on the far side of the Moon, or as we are now all accustomed to virtual meetings, [we could be] doing Skype on the Moon."

The project is separate from NASA's plans to fund a Nokia telecoms network on the Lunar surface, as well as its wider LunaNet project - which we profiled in detail earlier this year.

But ESA hopes to make the network interoperable with LunaNet, which has pitched itself as the core architecture of an Internet for space, and does not need to be tied to specific infrastructure (like how terrestrial Internet works with every telco).

"We don't want to have a closed-loop system," Viau said. "We are really looking at interoperability and open standards that can be developed with international collaboration."

LunaNet has also opened itself up to international involvement, so it will remain to be seen how the two initiatives interact and overlap.

ESA, as well as Italy and the UK’s space agencies, are partners with NASA on its flagship Artemis program, which aims to put a woman and person of color on the Moon by 2024, and establish a Moon base by the end of the decade. How this project will take part in that is still not entirely clear.

On the positioning side of Moonlight, ESA plans to make it available to any nation or corporation that pays to use it. But, Verhoef admitted, like the Earth has seen nations develop their own GNSS systems, it is likely some will do the same on the Moon.

Such redundancy is worth the headache, he said. “In the end, we are talking about safety of life of astronauts, so there is going to be an interest to have two systems in order to make sure that if there is a problem with one of the systems, the other can take over," he said, adding that work is ongoing under the United Nations to ensure that any such systems would be able to use the same receivers.

All of this connectivity opens up the far side of the Moon, where radio astronomers have long dreamed about setting up a giant telescope, free of signal interference.

Last month, in an entirely separate announcement, NASA's Lunar Crater Radio Telescope (LCRT) said that it had moved into Phase 2.

The space agency's Innovative Advanced Concepts division gave the project $500,000 to keep working on the proposal - which would use a huge Moon crater as a dish.

LCRT hopes to deploy DuAxel space robots which would built a wire mesh inside the crater, creating the largest radio telescope in the Solar System. This could provide unparalleled insights into the history of the universe.

"While there were no stars, there was ample hydrogen during the universe’s Dark Ages, hydrogen that would eventually serve as the raw material for the first stars," LCRT team member Joseph Lazio explained.

"With a sufficiently large radio telescope off Earth, we could track the processes that would lead to the formation of the first stars, maybe even find clues to the nature of dark matter."

Ensuring that Moonlight doesn't cast a shadow on such efforts is a problem for another day, though.

"Clearly the communication satellite is not going to be wanted to talk to the radio telescope," Parker said. "But it's not something that's going to become operational realistically until the next decade - but if it happens, there will have to be a solution."

Before then, there's still a lot of knowledge to be discovered on the Moon.

"The Moon is a repository of four and a half billion years of solar system history, but we've hardly begun to unlock its secrets," Parker said.